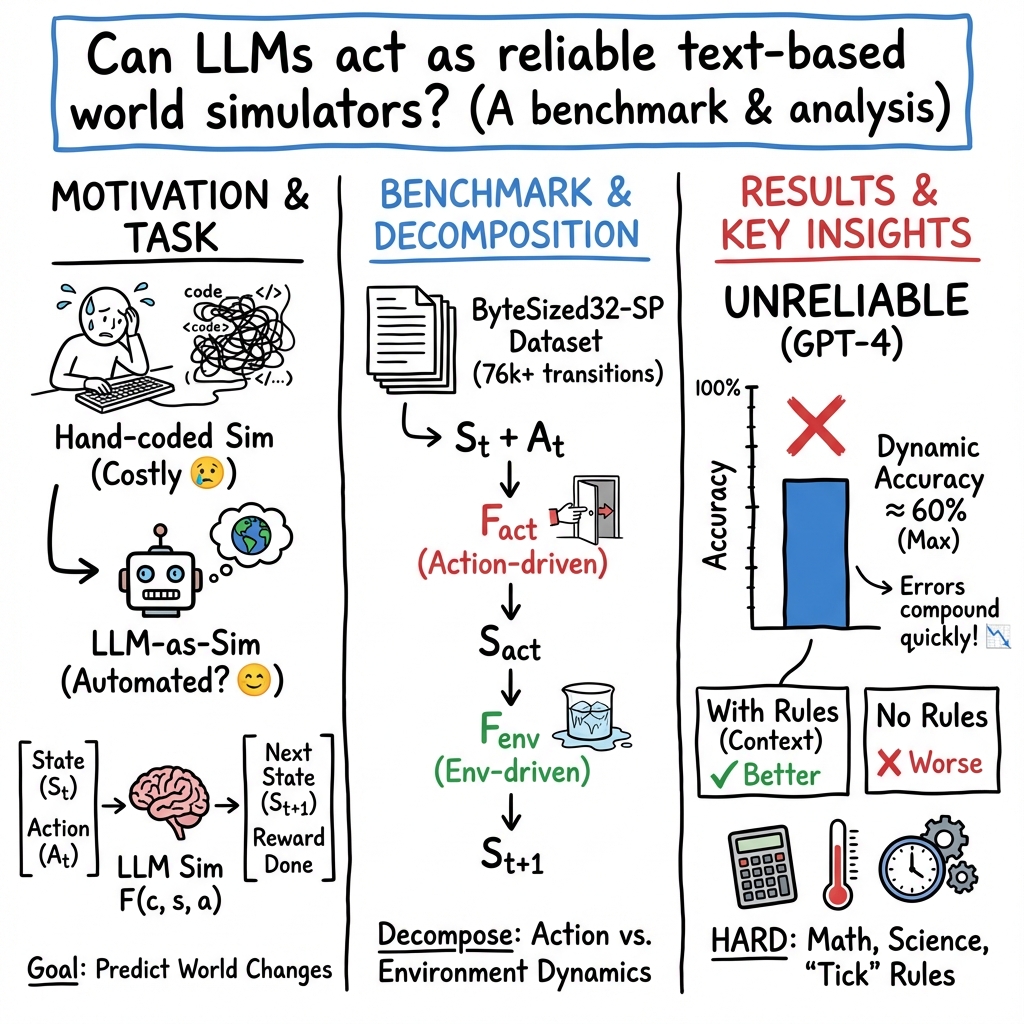

Can Language Models Serve as Text-Based World Simulators?

Abstract: Virtual environments play a key role in benchmarking advances in complex planning and decision-making tasks but are expensive and complicated to build by hand. Can current LLMs themselves serve as world simulators, correctly predicting how actions change different world states, thus bypassing the need for extensive manual coding? Our goal is to answer this question in the context of text-based simulators. Our approach is to build and use a new benchmark, called ByteSized32-State-Prediction, containing a dataset of text game state transitions and accompanying game tasks. We use this to directly quantify, for the first time, how well LLMs can serve as text-based world simulators. We test GPT-4 on this dataset and find that, despite its impressive performance, it is still an unreliable world simulator without further innovations. This work thus contributes both new insights into current LLM's capabilities and weaknesses, as well as a novel benchmark to track future progress as new models appear.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper asks a simple question with big consequences: Can today’s LLMs (like GPT-4) act like “world simulators” for text-based games? In other words, if you describe a game world in words and say what action a player takes, can the model correctly predict what happens next in that world?

To study this, the authors build a new benchmark (a testing setup) called ByteSized32-SP and measure how well GPT-4 predicts changes in game worlds step by step. Their short answer: GPT-4 is impressive, but not yet reliable as a world simulator.

What questions did the researchers ask?

They focused on five easy-to-understand questions:

- Can a LLM predict what changes when a player performs an action? (For example, “turn on the sink” makes the sink start running.)

- Can it also predict what the environment changes on its own after that action? (For example, once the sink is running, a cup under it starts to fill.)

- Can it tell if the player is closer to winning the game and how much “score” they earned?

- Do clear “game rules” help the model make better predictions?

- How close are the model’s predictions to what a human would predict?

How did they test it?

The dataset: ByteSized32-SP

- The team collected 76,369 “state transitions” (this means: a snapshot of the game world before an action, the action taken, and the snapshot after).

- These come from 31 small, science- or common-sense-themed text games (like mixing paint colors, heating water, or taking a photo).

- Everything is represented in simple, structured text (JSON), which is like a neatly labeled list of objects and their properties.

The idea of “state” and “actions”

- Think of the “state” as a detailed description of everything in the game world at a moment in time (e.g., “sink is on,” “cup is in the sink,” “cup is empty”).

- An “action” is what the player does (e.g., “turn on sink,” “put cup in sink”).

- After an action, the world changes to a new state.

Two kinds of changes

- Action-driven change: caused directly by what the player did (turning on the sink makes isOn=true).

- Environment-driven change: what the world does afterward on its own (water flows, so the cup starts filling).

The authors split the prediction task into three smaller tasks:

- Predict action effects (what changes immediately because of the action).

- Predict environment effects (what changes next because of how the world works).

- Predict game progress (score and whether the game is finished).

Two ways to output predictions

- Full state prediction: the model writes out the entire new world (everything, even what didn’t change).

- State difference prediction: the model only lists what changed (like a “change log” to keep things simpler).

What counts as success?

- The prediction is “correct” if the model’s output matches the true game engine’s next state.

- They looked at two types of steps:

- Static: nothing actually changes (the model should say “no change”).

- Dynamic: something does change (the model must say exactly what and how).

What did they find?

Here are the main results explained simply:

- Predicting direct action effects is easier than predicting environment effects:

- GPT-4 got up to about 77% correct on action-driven changes (dynamic cases).

- It was much worse on environment-driven changes (at best about 50% in dynamic cases).

- This means GPT-4 often misses what the world should keep doing after the player acts.

- Static is easier than dynamic:

- Saying “nothing changes” is easier than describing exactly how things change.

- Full vs difference outputs:

- For static steps, giving only the differences can help (there aren’t any differences, so it’s simpler).

- For dynamic steps, writing the full state sometimes works better because “difference” formatting adds extra complexity.

- Rules help a lot—and LLM-written rules can be as helpful as human-written rules:

- When the model is given clear game rules (what actions do, how scoring works), it performs better.

- Surprisingly, rules written by another LLM (from reading the game code) helped about as much as rules written by human experts.

- Without any rules, performance drops noticeably.

- Score and goal tracking looks good (with rules):

- With rules, GPT-4 correctly tracked game progress about 92% of the time.

- Without rules, this dropped to about 62%.

- Humans still win:

- In a small test on the hardest games, humans averaged 80% accuracy, while GPT-4 scored around 50% on the same sampled cases.

- Where GPT-4 struggles most:

- Changes that require arithmetic (like tracking temperature increases),

- Common sense (like camera focus and aperture behavior),

- Science knowledge (like how electricity or heat behaves).

- It’s better at simple true/false properties (like on/off), and worse at numbers or multi-step reasoning.

- Why single-step accuracy matters:

- If a model is right only 6 times out of 10 for each step, then after 10 steps in a row, the chance everything is still correct is less than 1 in 100. Errors pile up.

Why is this important?

This work shows that, as of now, LLMs—even strong ones like GPT-4—aren’t reliable enough to act as full “world simulators” for text-based environments. That’s important because many AI tasks (planning, robotics, virtual assistants, education games) need accurate “what happens next?” predictions to be safe and useful.

At the same time, the results are encouraging in a few ways:

- Clear instructions (“rules”) really help.

- Predicting direct action effects is already fairly strong.

- LLMs can even help write their own usable rules from code.

What could this change in the future?

- Better simulators: Researchers can use the new ByteSized32-SP benchmark to build and test new models that are better at step-by-step changes—especially the tricky environment-driven ones.

- Hybrid systems: Combining LLMs with tools (like simple calculators or physics rules) could fix many errors that require arithmetic or scientific knowledge.

- Safer applications: More reliable simulation could lead to better training environments for AI, safer planning tools, and smarter educational games—but only when prediction accuracy is high and errors don’t pile up.

- Transparency and testing: The structured, JSON-based setup helps diagnose exactly where models fail, guiding improvements in future models.

In short, this paper gives a careful, data-backed answer: LLMs are promising helpers, but they’re not yet dependable world simulators. The new benchmark provides a clear path to measure progress as models improve.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge Gaps, Limitations, and Open Questions

Based on the paper’s methods, results, and stated limitations, the following issues remain unresolved and point to concrete directions for future research.

Evaluation scope and setup

- Multi-step fidelity is unmeasured: only single-step prediction is evaluated, leaving open how simulators perform over long rollouts, with and without corrective mechanisms (e.g., self-consistency, constraint-checking, or state repair).

- Partial observability is not tested: models are always given the full ground-truth state; the ability to infer hidden state from natural-language observations (the O function) and maintain beliefs is unexplored.

- Stochastic dynamics are absent: environments appear deterministic; how models handle stochastic transitions and uncertainty (e.g., predicting distributions or calibrated confidences) is unknown.

- Generalization beyond text games is unexamined: no evaluation in richer or multimodal environments (e.g., physics engines, embodied worlds) to test transfer of world-modeling skills.

- External validity under realistic contexts is unclear: LLM-generated rules were produced with access to game code; performance when only noisy or incomplete natural-language documentation is available is not assessed.

Dataset and task design

- Local transition bias: transitions are at most one step from a gold trajectory; long-range dependencies, delayed effects, and rare or compound events are underrepresented.

- Action space coverage and compositionality are limited: ~7.4 verbs per game; generalization to unseen verbs, parameterized actions, or compositional instructions is untested.

- Distributional mismatch: experiments sub-sample equal numbers of static/dynamic transitions; performance under the natural (potentially skewed) distribution is not reported.

- Schema generalization and OOD properties: models are evaluated on a fixed JSON schema; robustness to unseen object properties, new relations, or evolving schemas is unknown.

- Scaling of state complexity: how accuracy and latency scale with larger worlds (more objects, properties, relations) and longer contexts is not quantified.

Modeling approach and alternatives

- No training or fine-tuning on transitions: only in-context prompting is tested; the gains from supervised fine-tuning, instruction-tuning, or reinforcement learning on ByteSized32-SP are unmeasured.

- Missing tool-use and hybrid methods: arithmetic, commonsense, and scientific reasoning are failure modes, but integration with tools (calculators, simulators), knowledge bases, or neurosymbolic validators is not explored.

- Environment-driven dynamics remain opaque: the taxonomy of dynamics (e.g., diffusion, flow, thermal equilibration, timers) is not formalized, and targeted methods to handle each class are not proposed or evaluated.

- Alternative state representations are untested: JSON full/diff are compared, but graph-structured states, declarative constraints, or programmatic transition functions with constrained decoding are not evaluated.

- Uncertainty and calibration are ignored: the simulator outputs point states; mechanisms to express, propagate, and evaluate uncertainty over next-state predictions are absent.

Metrics, analysis, and robustness

- Exact-match emphasis may be brittle: evaluation appears to hinge on exact state matches; graded metrics (per-property F1, invariant satisfaction, relational consistency) and violation types (e.g., illegal state changes) are not systematically reported.

- Robustness to prompt variations is unknown: sensitivity to context phrasing, number/choice of in-context examples, and rule verbosity/format is not analyzed.

- Rule quality is under-characterized: the “no obvious difference” between human and LLM rules lacks a deeper audit of rule completeness, correctness, and the specific error modes they induce.

- Adversarial and OOD robustness is untested: behavior under adversarial actions, conflicting rules, or out-of-domain games is not measured.

Human baseline and reproducibility

- Limited human study: small N (four author-annotators), biased game selection (worst for GPT-4), and normalization of GPT-4 performance to ~50% constrain conclusions about human–LLM performance gaps.

- API/version dependency: results rely on a specific closed model/version and JSON mode; reproducibility across model updates and portability to open-source models are uncertain.

Practicality and deployment

- Efficiency and cost not profiled: inference latency, token usage vs. state size, and cost-performance trade-offs for large-scale simulation are not analyzed.

- Safety and guardrails for simulators are unspecified: mechanisms to prevent unsafe or implausible state transitions (domain constraints, safety checkers) are not integrated or evaluated.

- Downstream utility is unquantified: the impact of simulator accuracy on agent planning and task completion (e.g., when plugged into planners or agents) is not empirically measured.

Open technical questions

- How to reliably model environment-driven transitions that require arithmetic, commonsense, and scientific laws (e.g., physics-informed priors, tool calls, constraint solvers)?

- What combinations of prompting, fine-tuning, tool-use, and constrained decoding most effectively reduce compounding errors over long horizons?

- Can models learn transferable, modular transition functions (per property/action class) that generalize across games and schemas?

- How to design evaluation suites that isolate specific dynamics (heat transfer, fluid flow, containment, timers) with controllable difficulty and clear success criteria?

- What uncertainty representations and decision-making strategies (e.g., belief tracking, ensemble rollouts) best mitigate simulator brittleness in planning loops?

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be deployed now, leveraging the paper’s dataset, task decomposition, and evaluation insights, while acknowledging current limitations (e.g., ~59.9% accuracy on dynamic transitions, compounding multi-step errors).

Industry

- LLM-Sim Testbench for AI product QA (software)

- Use ByteSized32-SP and the LLM-Sim task to systematically evaluate an LLM agent’s single-step state transition accuracy, broken down by action-driven vs environment-driven, static vs dynamic, and full-state vs state-diff outputs.

- Tools/Workflows: CI-integrated test harness; JSON-mode evaluation; per-property error analytics (e.g., arithmetic- and commonsense-sensitive properties).

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Access to LLMs and JSON mode; tasks with explicit state schemas; acceptance that multi-step reliability is low (error compounding).

- Action–Environment Decomposition Framework (software, robotics)

- Adopt the paper’s modular simulator decomposition (F_act, F_env, F_R) to isolate and improve the parts LLMs do better (action-driven transitions) while constraining or externalizing environment dynamics (which LLMs struggle with).

- Tools/Workflows: Middleware that routes action effects to LLMs and environment updates to deterministic engines; state-difference outputs for static transitions.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Clear, machine-readable object/property schemas; availability of rule/context descriptions; external simulators for environment physics when needed.

- Rule Synthesis Assistant from code (software)

- Use LLMs to auto-generate human-readable rule/context documentation from existing simulator code to improve LLM performance (the paper shows LLM-generated rules can match expert-written rules).

- Tools/Workflows: Code-to-rules pipelines; documentation checks; rule fidelity tests with ByteSized32-SP.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Access to source code; validation loop to catch inaccuracies; domain experts to sign off on critical systems.

- Simulator Guardrails and Fallbacks (games, robotics)

- Establish product safety policies that route environment-driven transitions (error-prone for LLMs) to deterministic modules, keeping LLMs in advisory/annotation roles for action-driven changes and user feedback.

- Tools/Workflows: Safety gating for environment updates; “LLM as explainer” rather than executor; hybrid orchestration.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Availability of physics/logic engines; defined escalation paths for uncertain predictions; policy reviews.

Academia

- Curriculum and lab modules on POMDPs and world modeling

- Integrate ByteSized32-SP into courses to teach POMDP concepts, state representation (JSON), single-step vs multi-step drift, and evaluation design.

- Tools/Workflows: “ByteSized32 classroom kit” with exercises on F_act vs F_env; error analysis labs on arithmetic/common-sense properties.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Open dataset access; reproducible prompts; clear grading rubrics.

- Baseline benchmark for LLM simulation research

- Use LLM-Sim and ByteSized32-SP to measure progress across models and prompting strategies; report per-property breakdowns and dynamic vs static transition accuracy.

- Tools/Workflows: Shared leaderboard; standardized JSON scaffolds; error taxonomy.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Community adoption; comparable model settings (e.g., temperature=0, JSON mode).

Policy

- Immediate guidance for safe deployment of LLM simulators in education and consumer products

- Apply the paper’s risk evidence (low reliability in environment-driven and multi-step settings) to discourage use in child-facing educational apps or safety-critical training simulators.

- Tools/Workflows: Risk assessment checklists referencing dynamic-transition accuracy; disclaimers; audit trails.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Institutional buy-in; governance processes; ability to enforce guardrails.

Daily Life

- Interactive fiction “Simulator Sanity Checker” for hobbyists

- A plugin to validate text-game transitions against rule sets, flagging environment-driven errors and arithmetic inconsistencies before publishing.

- Tools/Workflows: Twine/IF plugins that export/validate JSON states; property-level checks.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Adoption by IF tooling; rule schemas provided by creators; non-critical use cases.

Long-Term Applications

These applications require further research, scaling, or development to reach reliable deployment, given current performance limitations and error compounding over multiple steps.

Industry

- Neurosymbolic World Simulators (software, robotics, training)

- Hybrid systems combining LLMs with symbolic planners, calculators, physics engines, and domain solvers to handle environment-driven transitions and non-trivial properties (arithmetic, commonsense, scientific).

- Tools/Workflows: Tool-augmented LLMs; property-specific modules; planner integration (e.g., RAP-style MCTS).

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Reliable tool-use orchestration; improved grounding; stable interfaces for state updates.

- Text-based Digital Twins for operations (energy, manufacturing)

- High-fidelity text world models for process simulation and incident rehearsal; LLMs narrate and assist while deterministic modules govern state transitions.

- Tools/Workflows: Domain-specific state schemas; integration with telemetry; provenance and replay.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Accurate environment dynamics; domain data access; robust verification methods.

- Planner-in-the-loop Reasoning Engines (software, finance)

- Use RAP-like planning over LLM-driven world models to generate high-reward reasoning paths in complex tasks (plan generation, scenario analysis).

- Tools/Workflows: Monte Carlo Tree Search over structured states; reward shaping; self-consistency and self-correction.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: World model fidelity; scalable search; transparent reward functions.

Academia

- Property-targeted Curriculum Generator

- Automatically create datasets and tasks focused on failure modes (temperature updates, timers, aperture/focus, scientific toggles like “on”) to train and evaluate models.

- Tools/Workflows: Synthetic data pipelines; per-property difficulty tuning; active learning loops.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Labeling quality; transferability from synthetic tasks to real domains.

- Self-correcting multi-step simulation pipelines

- Develop iterative self-repair strategies that detect drift and re-synchronize with ground truth, reducing compounding error (e.g., trace-based validation, periodic rollbacks).

- Tools/Workflows: Error detectors; checkpoints; reconciliation protocols.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Reliable detectors; access to oracle states or safe anchors; tolerable latency costs.

Policy

- Standards and Certification for LLM-based simulators

- Establish sector-specific benchmarks, reporting formats, and minimum accuracy thresholds (especially for dynamic transitions) before deployment in training or decision-support.

- Tools/Workflows: Benchmark suites (extensions of ByteSized32); conformance tests; certification bodies.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Multi-stakeholder consensus; maintenance of public benchmarks; alignment with regulatory frameworks.

- Governance for safety-critical simulations (healthcare, energy, transportation)

- Policies requiring hybrid architectures (LLM + deterministic modules), auditability, and human oversight for simulators used in regulated domains.

- Tools/Workflows: Mandatory safety cases; documentation of rule contexts; incident reporting.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Regulatory harmonization; enforcement mechanisms; independent verification.

Daily Life

- Robust text-based learning labs and tutors (education)

- Once environment-driven accuracy improves, use LLM simulators to power interactive science labs and procedural training with reliable state transitions and explanations.

- Tools/Workflows: Tutor orchestration; concept-specific simulators; scaffolds for misconceptions.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Demonstrated reliability on scientific properties; age-appropriate safety controls; empirical validation.

- Personal process simulators (productivity)

- Simulate complex tasks (e.g., cooking workflows, DIY) with accurate state progression and contingencies; LLM narrates, plans, and adapts.

- Tools/Workflows: Task schemas; error bounding; user-in-the-loop corrections.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Improved commonsense and arithmetic handling; calibrated uncertainty; fail-safe design.

Glossary

- Action-driven transition: A change in the game state caused directly by the agent’s action. "the action-driven transition is that the sink is turned on (isOn=true) after taking the action turn on sink"

- Action-driven transition simulator: The component that predicts the immediate state change caused by an action. "Action-driven transition simulator predicts given , , and "

- Action rules: Contextual rules that define how actions affect the state. "action rules describing the effect of each action on the game state"

- Agent policies: Strategies or plans that an agent follows to act in the environment. "then uses a dedicated planning algorithm to decide on agent policies"

- ByteSized32: A benchmark/dataset of reasoning-focused text games and transitions. "a new benchmark, called ByteSized32, containing a dataset of text game state transitions and accompanying game tasks"

- ByteSized32-SP: The state-transition subset of ByteSized32 used for simulation evaluation. "Our dataset, ByteSized32 (ByteSized32-SP), consists of 76,369 transitions"

- Completion indicator function: A binary function signaling whether a task is completed. " denotes the binary completion indicator function"

- Context message: Natural language instructions and rules that describe goals and action semantics. "Each game also includes a context message, , that provides additional information to the model."

- Dynamic transition: A transition where the state changes non-trivially. "Dynamic and static denote whether the game object properties and game progress should be changed"

- Environment-driven transition: A change in state caused by environmental dynamics, not directly by the agent’s action. "the environment-driven transition is that water fills up the cup in the sink when the sink is on"

- Environment-driven transition simulator: The component that models changes due to environmental dynamics. "Environment-driven transition simulator predicts given and "

- Full State Prediction: Outputting the entire next state rather than only changes. "Full State Prediction: The LLM outputs the complete state."

- Game progress: The agent’s status relative to the goal, including reward and termination. "Game Progress: the status of the agent w.r.t. the overall goal, consisting of the current accumulated reward, whether the game has terminated, and whether the overall goal has been achieved."

- Game progress simulator: The component that predicts reward and whether the game is complete. "Game progress simulator predicts the reward and the game completion status "

- Goal-conditioned: A formulation where the policy or model conditions on an explicit goal. "Each text environment can be formally represented as a goal-conditioned partially observable Markov decision process (POMDP)"

- Gold-label: The authoritative or target trajectory/labels used as ground truth. "following the gold-label goal-following trajectory provided with each game"

- In-context learning: Using examples within the prompt to guide model behavior without weight updates. "we evaluate the performance of a model on the LLM-Sim task using in-context learning."

- JSON mode: A constrained generation setting where the model must output valid JSON. "We also turn on the JSON mode of both models, which ensures that the model gives a valid JSON response."

- JSON schema: A structured format specification used to scaffold and validate state representations. "We make use of structured representations in the JSON schema as a scaffold"

- LLM-as-a-Simulator (LLM-Sim): The task of using an LLM to directly simulate state transitions and progress. "We propose a prediction task, which we call LLM-as-a-Simulator (LLM-Sim)"

- LLM priors: Prior knowledge encoded in a LLM used to instantiate a world model. "it constructs a world model using LLM priors"

- Neurosymbolic: Approaches that integrate neural models with symbolic representations or reasoning. "The first is neurosymbolic: a number of efforts use LLMs to generate code in a symbolic representation"

- Object properties: Attributes and relations of objects comprising the state. "Object Properties: a list of all objects in the game, along with each object's properties (e.g., temperature, size) and relationships to other objects"

- Object rules: Rules that define the meaning and dynamics of object properties. "object rules describing the meaning of each object property and whether they are affected by the game's underlying dynamics"

- Observation function: The mapping from state to observations received by the agent. " denotes the observation function"

- Partially observable Markov decision process (POMDP): A framework where the agent has incomplete state information and must act under uncertainty. "Each text environment can be formally represented as a goal-conditioned partially observable Markov decision process (POMDP)"

- Reward function: A mapping from state-action pairs to scalar rewards. " denotes the reward function"

- Scoring rules: Rules describing how reward is accrued and win/loss conditions. "scoring rules describing how an agent earns reward and the conditions under which the game is won or lost"

- Single-step prediction: Predicting the next state and outcomes given the current state and action only one step ahead. "the LLM always performs a single-step prediction."

- State difference prediction: Outputting only the changes between consecutive states rather than the full state. "State Difference Prediction: The LLM outputs only the difference between the input and output states."

- State space: The set of all possible states in the environment. " denotes the state space"

- Static transition: A transition where the state remains unchanged. "a dynamic action-driven transition and a static environment-driven transition."

- Transition dynamics: How states change in response to actions and environmental processes. "the transition dynamics between states depend primarily on the verb used in the action"

- Transition function: The mapping that specifies the next state given the current state and action. " denotes the transition function"

- World modeling: The construction or use of models that capture environment states and their evolution. "world modeling and simulation"

- World simulator: A system that predicts how actions change world states. "Can current LLMs themselves serve as world simulators"

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.