Learn To be Efficient: Build Structured Sparsity in Large Language Models

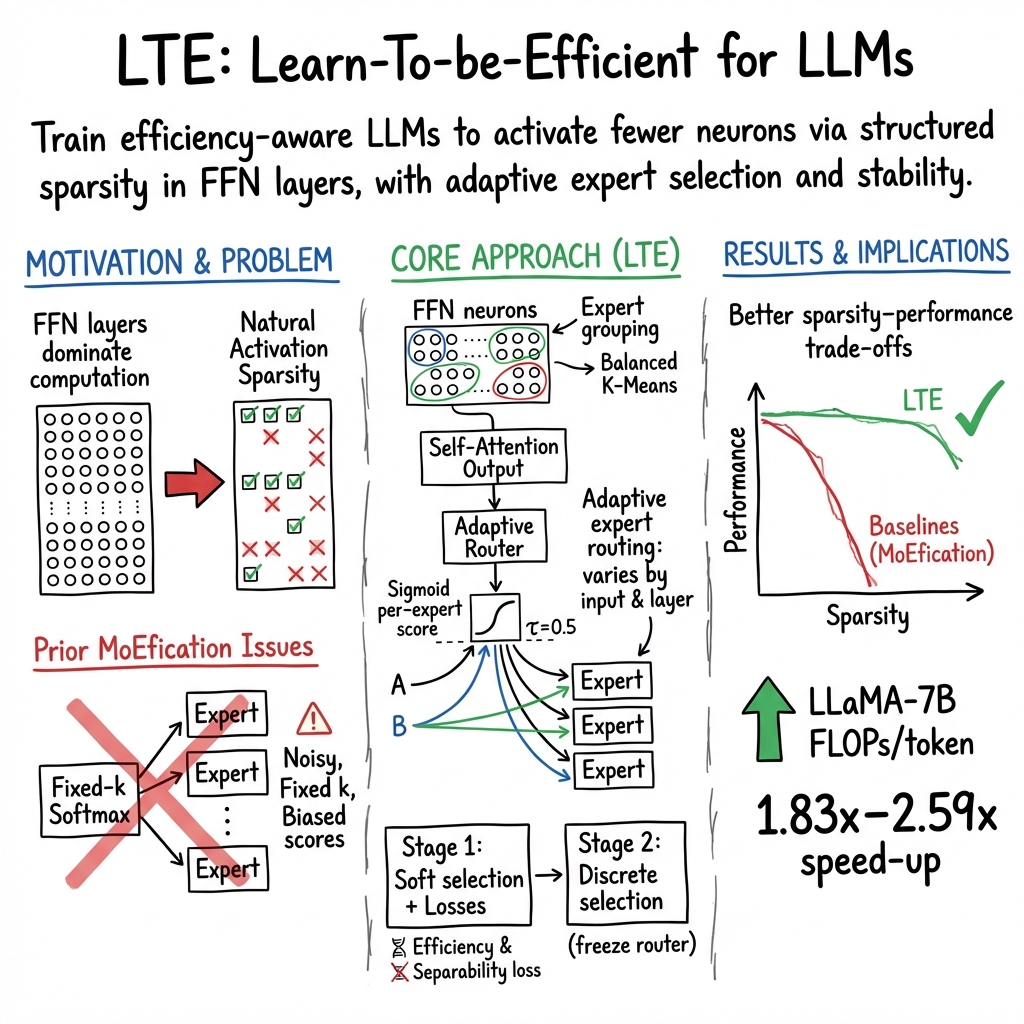

Abstract: LLMs have achieved remarkable success with their billion-level parameters, yet they incur high inference overheads. The emergence of activation sparsity in LLMs provides a natural approach to reduce this cost by involving only parts of the parameters for inference. However, existing methods only focus on utilizing this naturally formed activation sparsity in a post-training setting, overlooking the potential for further amplifying this inherent sparsity. In this paper, we hypothesize that LLMs can learn to be efficient by achieving more structured activation sparsity. To achieve this, we introduce a novel training algorithm, Learn-To-be-Efficient (LTE), designed to train efficiency-aware LLMs to learn to activate fewer neurons and achieve a better trade-off between sparsity and performance. Furthermore, unlike SOTA MoEfication methods, which mainly focus on ReLU-based models, LTE can also be applied to LLMs like LLaMA using non-ReLU activations. Extensive evaluation on language understanding, language generation, and instruction tuning tasks show that LTE consistently outperforms SOTA baselines. Along with our hardware-aware custom kernel implementation, LTE reduces LLaMA2-7B inference latency by 25% at 50% sparsity.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Plain-Language Summary of “Learn To be Efficient: Build Structured Sparsity in LLMs”

What is this paper about?

This paper is about making LLMs faster and cheaper to use without hurting their accuracy. LLMs like GPT and LLaMA have billions of tiny parts (called “neurons”) that do math to understand and generate text. That’s powerful—but also slow and costly. The authors introduce a new method called Learn-To-be-Efficient (LTE) that teaches these models to use fewer neurons in a smart, organized way, so the models run faster while staying accurate.

What questions does the paper try to answer?

The paper focuses on three simple questions:

- How can we group neurons that often work together into small teams (“experts”)?

- How can we train a “router” that chooses which expert teams should work for each word or sentence, without breaking the model’s accuracy?

- How can the model flexibly choose the right number of experts for different inputs and different layers, instead of always using the same amount?

It also asks: Can we do all this even for models that use “soft” activations (like LLaMA’s SwiGLU), which don’t naturally turn neurons off, without changing them to ReLU (which can hurt performance)?

How does the method work? (Simple explanation and analogies)

Think of an LLM like a very large school:

- Neurons are students.

- Experts are clubs of students who do similar tasks together.

- A router is a coach who decides which clubs should work on a particular assignment (like understanding a sentence or predicting the next word).

The key idea: Many neurons don’t need to work all the time. If we can figure out which clubs are truly helpful for each input, we can skip the rest and go faster.

Here’s what LTE does:

- Groups neurons into experts: It uses a clustering method (like grouping students who have similar skills) so each expert has about 32 neurons.

- Trains a better router: Instead of using a method that forces all expert scores to “compete” and sum to 1 (Softmax), which often picks just one expert and hurts accuracy, LTE uses Sigmoid scores where each expert gets its own independent score. Then it uses a simple threshold (like “only pick experts with a score above 0.5”) so the number of chosen experts can change depending on the input.

- Two-stage training (like practice before the real game):

- Stage 1: Soft selection. Let all experts contribute, but give stronger experts bigger scores. Two helpful “nudges” are added:

- Efficiency loss: Encourages the router to give smaller scores overall, so fewer experts are used.

- Separability loss: Pushes expert scores to be clearly above or below the threshold, making it easier to decide who gets picked.

- Stage 2: Hard selection. Freeze the router and actually pick only the experts whose scores pass the threshold. Then fine-tune the model so it adapts to using fewer experts.

Why not the old way? A commonly used method (“noisy top-k Softmax”) tends to push almost all trust into one expert (the “winner”), which drops accuracy. LTE avoids that by scoring experts independently and using a threshold.

What did the experiments show?

The authors tested LTE on four well-known models (RoBERTa-base, RoBERTa-large, GPT2-Medium, LLaMA-7B) and 11 datasets covering both understanding tasks (like classifying sentence meaning) and generation tasks (like summarizing text).

Main results:

- Natural Language Understanding (NLU): LTE reached very high sparsity (using 80–95% fewer neurons in certain layers) with little or no accuracy drop compared to the original model.

- Natural Language Generation (NLG): On LLaMA-7B, LTE reduced the amount of computation (FLOPs) by about 1.83x to 2.59x while keeping output quality high. That means the model runs roughly twice as fast in terms of math work per token.

- Works with soft activations: Many older methods needed to replace “soft” activations (like SwiGLU) with ReLU to get sparsity, which can hurt performance. LTE achieves speed-ups without changing the activations.

- Adapts across layers: Different layers of the model learned different levels of sparsity. Some layers used many experts; others used few. This flexible usage helps keep quality high.

Why is this important?

- Faster models: Using fewer neurons means quicker responses—great for chatbots, apps, and any tool that needs speed.

- Lower cost and energy: Running fewer computations cuts costs and saves electricity, which is good for the environment.

- Better access: Smaller companies, schools, and researchers can use strong models without needing huge computing power.

What could this mean for the future?

LTE shows that we can train models not just to be accurate, but also to be efficient. That can inspire new training methods that make powerful AI more practical, greener, and widely available. It’s a step toward smarter, more responsible AI systems that do more with less.

Knowledge Gaps

Below is a single, concise list of the paper’s knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions that future work could address:

- Real-world efficiency is only reported in FLOPs; no wall-clock latency, throughput, or energy measurements on actual hardware (e.g., A100/4090 GPUs, CPUs) or end-to-end serving systems.

- No implementation details or benchmarks for sparse/structured kernels that exploit expert-level chunking in FFN layers; unclear how routing-induced branching affects GPU efficiency, warp divergence, and kernel fusion.

- Memory and systems aspects are unmeasured: VRAM footprint, memory bandwidth/IO behavior, cache locality, and compatibility with tensor/pipeline parallelism and KV-cache optimizations.

- The router’s runtime overhead is approximated by FLOPs (~1%) but lacks measured latency and memory overhead, and its effect on achievable batch sizes and throughput.

- The method uses a fixed global threshold (τ=0.5) without sensitivity analysis or a principled scheme to meet a target compute budget; no controller to calibrate τ (or λ) per-layer/per-input to satisfy latency constraints.

- Hyperparameter sensitivity is largely unexplored: λ1 (efficiency), λ2 (separability), router learning rate, and expert size; no guidance for robust defaults across models and tasks.

- The separability loss 1/(G−τ)2 risks gradient explosion near τ; no mitigation (e.g., clipping, bounded penalties) or stability analysis for training dynamics.

- Expert grouping is fixed to balanced K-Means on W1 columns with 32-neuron experts; no exploration of alternative grouping criteria (e.g., activation correlations on data, Fisher information, supervised grouping) or expert size trade-offs.

- Clustering cost and scalability for large models (dFFN in tens of thousands) are unreported; no analysis of how often grouping should be recomputed as the model adapts.

- Stage-1 soft routing followed by Stage-2 hard thresholding may induce distribution shift; no quantitative analysis of adaptation cost, convergence diagnostics, or alternatives (e.g., straight-through estimators, annealed thresholds).

- Theoretical understanding is limited: no guarantees that Sigmoid + efficiency/separability losses avoid dead/degenerate experts, or conditions ensuring convergence to useful sparse allocations.

- Expert utilization and balance are not analyzed; potential overuse of a few experts and underuse of others (classic MoE capacity imbalance) is unaddressed, and no regularizers for load balancing are proposed.

- Adaptive expert selection per token/layer is proposed, but runtime scheduling implications (load balancing, stream priorities) in multi-device or distributed inference are not discussed.

- Evaluation is confined to medium-scale models (RoBERTa, GPT2-M, LLaMA-7B); no evidence the approach scales to larger LLMs (e.g., LLaMA-70B, GPT-NeoX) or instruction-tuned/RLHF chat models.

- Task coverage is limited (GLUE, E2E, XSum, WikiText-103); no assessment on long-context tasks, multi-turn dialogue, code generation, multilingual/cross-lingual benchmarks, or safety-critical domains.

- Quality metrics are narrow (accuracy, ROUGE-L, perplexity); no human evaluation or broader measures (factuality, coherence, toxicity, calibration, robustness to distribution shift).

- Interaction with other efficiency methods (quantization, structured pruning, token pruning, low-rank adapters, KV-cache compression) is untested; potential synergies/conflicts are unknown.

- The paper critiques noisy top-k Softmax routing but does not compare against modern router variants (e.g., Z-loss, auxiliary load-balancing losses, temperature scaling, stochastic gates) under MoEfication.

- The approach focuses on FFN layers; potential extension to attention modules (e.g., gating heads, block-sparse attention) is unexplored.

- There is no method to precisely target a desired sparsity or FLOPs budget during training/inference, beyond indirectly tuning λ1 or τ; an explicit budget-aware controller is missing.

- Robustness/generalization of trained routers to new domains/tasks (transfer without re-training) is not evaluated; effects on out-of-distribution inputs and adversarial robustness are unknown.

- The impact of LTE on interpretability (what experts represent, consistency across tasks/layers) is not investigated; whether learned experts capture stable semantic functions remains unclear.

- Training cost is unreported: GPU-hours, additional overhead versus standard fine-tuning, data requirements for stable router learning—especially for large models.

- Reproducibility and code availability are not detailed; exact expert counts per layer, clustering seeds, and implementation for SwiGLU grouping (choice of W vs. V) need clarification for faithful replication.

- Potential bias/fairness risks from adaptive gating (e.g., under-activating experts for minority dialects or rare patterns) are unexamined; no safety analysis or mitigation strategies.

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following applications leverage the paper’s LTE algorithm and structured activation sparsity to deliver deployable improvements in inference efficiency, cost, and latency, while preserving task performance in many settings.

- Industry (software/cloud): Cost- and latency-optimized LLM inference

- Use case: Fine-tune existing LLMs (e.g., LLaMA-7B, GPT-2 Medium, RoBERTa) with LTE to achieve 1.8x–2.6x FLOPs reduction in generation tasks and 80–95% FFN sparsity on NLU tasks without accuracy drop.

- Workflow:

- MoEfy FFN layers via parameter clustering (balanced K-Means) into 32-neuron experts.

- Train Sigmoid routers with efficiency and separability losses (stage 1), then switch to thresholded discrete routing and adapt the model (stage 2).

- Export to inference runtimes supporting conditional execution of experts; tune the threshold τ and efficiency coefficient λ1 to meet latency/SLOs.

- Tools/products: Hugging Face Transformers integration; custom CUDA/Triton kernels for chunked FFN execution; vLLM/TGI or ONNX Runtime custom ops for router gating.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Wall-clock gains depend on hardware kernels that skip non-selected expert chunks; router overhead (~1% of FFN FLOPs) remains low; availability of task-specific fine-tuning data; careful τ selection (default 0.5) and λ1 tuning to balance quality vs sparsity.

- Energy and sustainability: Reduced energy per query in data centers

- Use case: Lower total energy footprint for high-volume LLM services (chat, search, RAG) by activating fewer neurons.

- Tools/products: “Green AI” reporting dashboards showing FLOPs/token and estimated energy/token; integration with sustainability KPIs.

- Assumptions/dependencies: FLOPs reductions translate to energy savings if kernels and schedulers actually skip work; workload mix and model size affect realized savings.

- Mobile and edge AI: Faster, more feasible on-device assistants

- Use case: Deploy LTE-trained models on laptops, tablets, and high-end smartphones to improve responsiveness and battery life for summarization, drafting, and offline Q&A.

- Workflow: Combine LTE with quantization (e.g., GPTQ) to fit memory/compute constraints; tune τ per device profile; use adaptive expert selection for variable inputs.

- Tools/products: Core ML/NNAPI/TensorRT runtimes with conditional expert execution; edge-specific model cards with measured sparsity and latency.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Edge runtime support for conditional execution and structured sparsity; memory bandwidth and cache behavior do not negate gains.

- Healthcare: Faster clinical summarization and triage note generation

- Use case: Reduce latency in clinical documentation summarization or triage assistance while maintaining accuracy on trained tasks.

- Tools/products: LTE-enabled summarizers integrated in EHR assistants.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Domain fine-tuning data available; rigorous validation for safety/compliance; performance checks to ensure soft activation preservation (avoid ReLU swap).

- Finance and enterprise: Accelerated document Q&A and reporting

- Use case: Speed up long-form summarization and interactive analysis of filings, earnings calls, and contracts with cost-efficient inference.

- Tools/products: LTE-optimized RAG pipelines; SLA-aware routers that adapt expert activation under load.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Router stability and accuracy under diverse inputs; compatibility with existing retrieval and caching systems.

- Education: Real-time tutoring, grading assistance, and content feedback

- Use case: Lower-cost educational LLM services with better responsiveness for interactive learning tools.

- Tools/products: LTE-trained models embedded in LMS platforms; threshold knobs to meet classroom device performance.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Task-aligned fine-tuning; quality monitoring for high-sparsity regimes.

- MLOps and platform engineering: SLO-aware inference control

- Use case: Dynamically tune τ and λ1 at deploy time to meet latency/throughput targets, with observability into layer-wise sparsity.

- Tools/products: Sparsity dashboards showing per-layer activation rates; autoscaling policies incorporating structured sparsity.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Robust runtime APIs to adjust routing; monitoring to detect quality degradation; compatibility with multi-tenant scheduling.

- Academia and research: Efficiency-aware training benchmarks and methods

- Use case: Use LTE as a baseline to study efficiency-aware objectives and adaptive sparsity across layers; test soft activation compatibility vs ReLU swaps.

- Tools/products: Reproducible scripts for neuron clustering, router training, and sparsity visualization; datasets as in GLUE, XSum, E2E, WikiText-103.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to compute for stage-1 and stage-2 training; alignment to downstream tasks; fair comparisons with quantization/pruning baselines.

Long-Term Applications

The following applications extend the paper’s ideas into broader systems, hardware, and methodological innovations, requiring further research, scaling, or ecosystem development.

- Hardware–software co-design for structured sparsity

- Use case: GPU/TPU/NPU kernels and memory layouts optimized for skipping expert chunks with minimal overhead; router execution fused into FFN blocks.

- Products: Next-gen accelerators with native conditional-execution primitives; compiler passes (TVM/XLA/Triton) that map expert groups to contiguous memory tiles.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Vendor support; stable sparsity patterns; end-to-end benchmarks that align FLOPs savings with wall-clock gains.

- QoS-aware, load-adaptive routing

- Use case: Dynamic τ and λ1 control loops (RL or control-theoretic) to maintain latency and accuracy targets under varying load and input mix.

- Products: “Quality knobs” exposed to platform operators; policies that trade computation budget across layers and requests in real time.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Reliable quality metrics and feedback; guardrails to prevent oscillation; alignment with fairness in multi-tenant scenarios.

- Compound efficiency stacks: LTE + quantization + pruning + distillation

- Use case: Combine structured activation sparsity with weight sparsity and low-precision arithmetic for multiplicative speedups and memory savings.

- Products: Unified efficiency toolchains with joint training objectives; pipelines that pick optimal combinations per task and hardware.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Interactions among methods don’t degrade quality; kernels support mixed optimizations; careful calibration across tasks.

- Pretraining and architecture design with efficiency-aware objectives

- Use case: Train new LLMs from scratch with built-in adaptive sparsity and Sigmoid threshold routing, avoiding MoEfication retrofitting.

- Products: Architectures that natively encode expert groups in FFN blocks and learn routing early; curricula for sparsity development.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Large-scale pretraining resources; stability of efficiency losses at scale; generalization across diverse domains.

- Automated expert grouping beyond K-Means

- Use case: Learn neuron-to-expert assignments end-to-end (e.g., via differentiable clustering or gating) to better capture functional similarity.

- Products: Libraries for learned expert partitioning; analysis tools to interpret expert semantics.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Training stability; avoidance of collapse (single-expert dominance); scalability to billions of parameters.

- Standards and policy: Energy and efficiency reporting for LLM services

- Use case: Establish norms for reporting FLOPs/token, energy/query, and sparsity metrics; incorporate efficiency-aware training into procurement guidelines.

- Products: Auditing frameworks; certifications for “efficiency-aware AI.”

- Assumptions/dependencies: Industry adoption; reliable measurement across heterogeneous hardware; integration with environmental regulation.

- Edge deployment of larger models

- Use case: Push 7B-class models to constrained devices with acceptable latency via structured sparsity and selective expert activation.

- Products: LTE-powered edge SDKs with per-device profiles; battery-aware routing policies.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Memory and thermal limits; robust local kernels; content safety and privacy on-device.

- Developer tooling and observability

- Use case: “Sparsity dashboards” and profilers to visualize expert selection, per-layer activation, and quality impacts; A/B testing harnesses for τ/λ1 tuning.

- Products: IDE plugins and CI/CD integrations for efficiency-aware model delivery; auto-tuning services for deployment contexts.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Accurate instrumentation; standardized metrics; compatibility with diverse model architectures and runtimes.

- Domain-specific, safety-critical integrations (e.g., autonomous systems)

- Use case: Language interfaces in robotics or driver assistance improved for latency; controlled routing ensuring predictable compute budgets.

- Products: Safety-certified LTE variants; deterministic routing modes for real-time systems.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Extensive validation; clear safety envelopes; task formulations where LLMs are appropriate and constrained.

Notes on feasibility across applications:

- LTE’s benefits rely on translating structured activation sparsity into real wall-clock speedups; this depends on kernels that skip work efficiently and on memory/system-level constraints.

- Accuracy-preserving sparsity varies by dataset and task; thresholds and loss weights must be tuned, and soft activations should generally be preserved (the paper observes ReLU swaps can hurt).

- Router training stability is critical; the paper’s Sigmoid threshold routing plus two-stage training avoids noisy top-K issues, but production-grade implementations need careful monitoring.

- Distributed inference and multi-GPU setups may require additional engineering to maintain gains when experts are sharded or pipelined.

Glossary

Activation sparsity: The phenomenon where some neurons in a neural network remain inactive, or "sparse", allowing for more efficient processing. Example: "The emergence of activation sparsity in LLMs provides a natural approach to reduce this cost by involving only parts of the parameters for inference."

Denseenum: A compact enumeration environment with reduced spacing, used for listing items. Example: "\begin{denseenum} \item Activation sparsity... \end{denseenum}"

Feed Forward Network (FFN): A type of neural network architecture where connections between nodes do not form cycles. Example: "During LLM inference, Feed Forward Network~(FFN) layers have been one primary bottleneck."

Mixture of Experts (MoE): A model that divides a large network into multiple smaller networks ("experts") and learns which expert to use. Example: "Mixture of Experts (MoE) was proposed by~\citeauthor{6797059} a few decades ago."

MoEfication: The process of converting FFN layers into MoE layers to facilitate better activation sparsity and efficient computation. Example: "SOTA MoEfication methods focus on utilizing naturally formed sparsity."

Sparse: Relating to matrices or vectors with a significant number of zero values, enabling efficient computation. Example: "The efficiency loss penalty...driving routers to selectively allocate lower expert scores to less important experts."

SwiGLU: A variant of the GLU activation function used in models like LLaMA, capable of handling soft activations. Example: "for LLMs with soft activation functions, such as SwiGLU in LLaMA, existing works have to replace activation with ReLU."

Top-k Softmax routing: A method used in mixture of experts models for selecting a subset of experts, using a softmax layer to compute selection probabilities. Example: "existing widely used Top-k Softmax routing can lead to a severe accuracy drop."

Two-stage training mechanism: A training process that involves two distinct phases to improve model performance or capabilities. Example: "LTE adopts a threshold-based Sigmoid routing strategy to select experts and employs a two-stage training mechanism."

Warm up ratio: A hyperparameter in training that defines the duration for gradually increasing the learning rate from 0 to its initial value. Example: "Warm up ratio & 0.06 & 0.06."

Swish: An activation function that is usually defined as , used in advanced neural network models. Example: "FFN layers using SwiGLU (e.g., LLaMA), there are two linear networks to calculate neuron values."

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.