Markerless Motion Capture and Biomechanical Analysis Pipeline

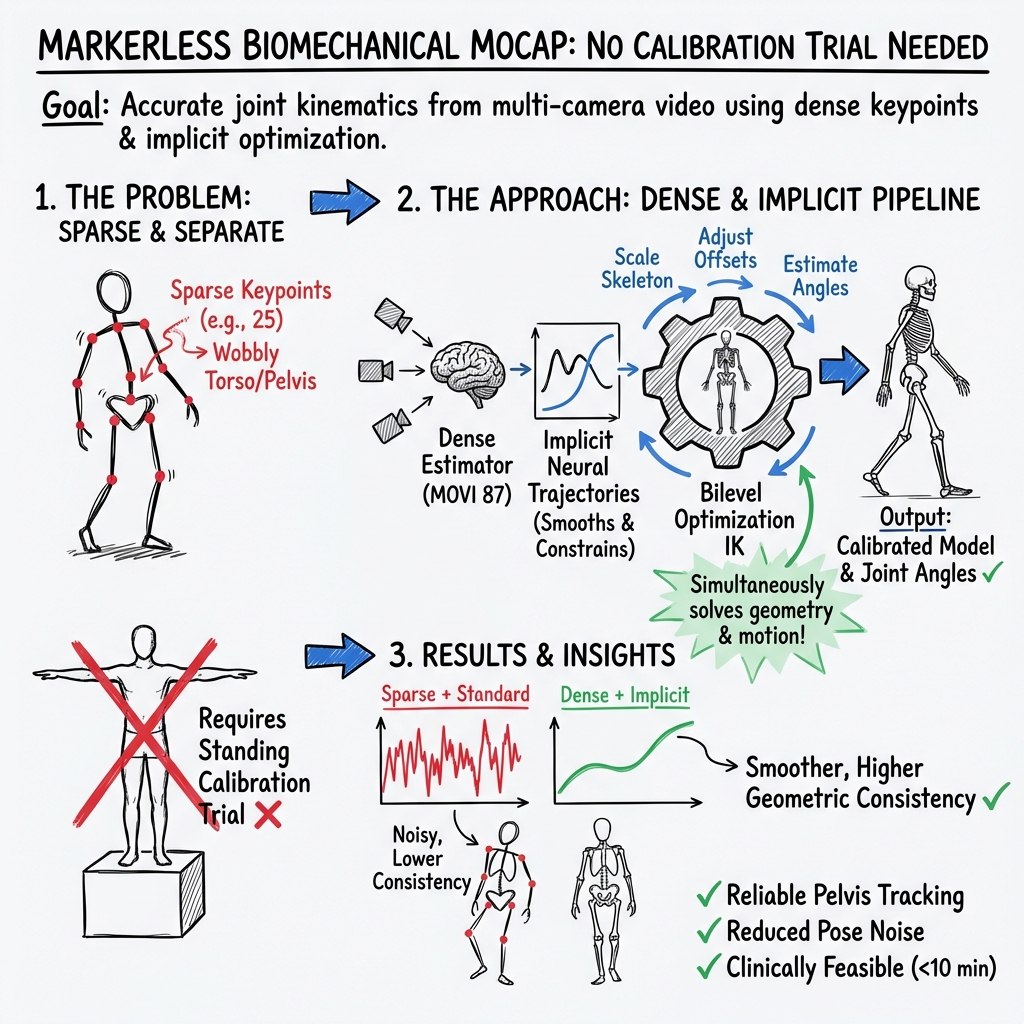

Abstract: Markerless motion capture using computer vision and human pose estimation (HPE) has the potential to expand access to precise movement analysis. This could greatly benefit rehabilitation by enabling more accurate tracking of outcomes and providing more sensitive tools for research. There are numerous steps between obtaining videos to extracting accurate biomechanical results and limited research to guide many critical design decisions in these pipelines. In this work, we analyze several of these steps including the algorithm used to detect keypoints and the keypoint set, the approach to reconstructing trajectories for biomechanical inverse kinematics and optimizing the IK process. Several features we find important are: 1) using a recent algorithm trained on many datasets that produces a dense set of biomechanically-motivated keypoints, 2) using an implicit representation to reconstruct smooth, anatomically constrained marker trajectories for IK, 3) iteratively optimizing the biomechanical model to match the dense markers, 4) appropriate regularization of the IK process. Our pipeline makes it easy to obtain accurate biomechanical estimates of movement in a rehabilitation hospital.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Overview

This paper is about a new, easy-to-use way to measure how people move using videos instead of attaching reflective stickers or sensors to their bodies. This “markerless motion capture” pipeline turns videos from several cameras into accurate estimates of joint angles and walking measurements. The goal is to make movement testing faster, cheaper, and more practical in places like rehabilitation hospitals.

What questions were they trying to answer?

The researchers wanted to find the best recipe for turning videos into trustworthy body movements. In plain terms, they asked:

- Which dots on the body should the computer look for in each video frame: a small set (few dots) or a dense set (many dots, especially on the pelvis and spine)?

- What’s the best way to rebuild smooth 3D paths of those dots over time: a simple geometry trick or a smarter, smoother method?

- How can we fit a digital skeleton to those 3D dots to get joint angles without asking the person to stand still for a separate “calibration” pose?

- What settings and model tweaks make the fits stable and realistic?

How did they do it?

To keep things simple, think of this process like following virtual “stickers” on the body through time and then fitting a puppet (a digital skeleton) to those stickers.

- They recorded people walking with 8–10 synchronized cameras in a clinic room. The cameras were calibrated so the system knew exactly where each camera was and how it saw the room.

- A computer-vision model found “keypoints” (virtual stickers) on the body in each camera view. The team tested:

- A dense set with 87 keypoints (including many on the pelvis and torso).

- A common smaller set with about 25 keypoints (fewer dots on the torso).

- To rebuild 3D paths of each keypoint through time, they compared two approaches:

- Robust triangulation: like drawing lines from each camera to find where they meet in space, done frame by frame.

- Implicit smooth curves: like fitting a flexible, smooth path through time for each point (think of bending a smooth ruler along a path so it doesn’t zig-zag). This method uses a small neural network to make the paths smooth and anatomically reasonable.

- They then fitted a digital skeleton to those 3D keypoint paths using “inverse kinematics” (IK). IK is like moving the puppet’s joints until its virtual markers line up with the dots from the videos. Their IK method could:

- Scale the skeleton to match each person’s body.

- Adjust marker positions slightly to match anatomy.

- Solve for the joint angles over time.

- Do all of this without a separate “stand still” calibration.

- They checked accuracy in several ways:

- Geometric consistency: do the fitted model’s projected dots line up with the dots seen by the cameras?

- Noise: are the joint angles smooth, without jitter?

- Joint realism: do joints stay within realistic ranges?

- Real-world comparison: are step length, stride length, and step width close to what a pressure mat (GaitRite) measured?

They tested this on 25 people in rehab with different conditions (like stroke or prosthetic limb use), capturing over a million video frames, to make sure it worked in a real-world hospital setting.

What did they find?

- More dots on the body is better: Using the dense 87-keypoint set (especially around the pelvis and torso) made joint angle estimates much more stable and realistic than using a sparse 25-keypoint set. With too few torso dots, the pelvis and hips were underconstrained and got wobbly.

- Smooth 3D paths beat simple geometry: The “implicit smooth curves” method for rebuilding 3D trajectories reduced joint angle jitter and matched the video data better than robust triangulation.

- No stand-still calibration needed: Their IK approach, which solves body size, marker placement, and joint angles together, worked well and fit smoothly into a clinical workflow.

- Tuning the model helped: Refining where virtual markers sit on the digital skeleton and using “soft” joint limits (gentle constraints rather than hard walls) prevented weird or impossible poses and improved fits.

- It’s accurate enough for clinic use: When they compared step length, stride length, and step width from the videos to a reference walkway, the typical differences were about 8–13 mm (around 1 cm), which is quite precise. The system also picked up meaningful changes in gait, like better ankle lifting with electrical stimulation or changes caused by a brace.

Why this matters

This pipeline shows that accurate movement measurement can be done with just cameras and smart software—no sticky markers, no special suits, and no lengthy setup. That means:

- Faster, easier testing in hospitals and clinics, including for people who can’t stand still for calibration.

- Better tracking of patient progress and responses to treatments.

- More sensitive research studies that can pick up small but important changes in how people move.

- A practical path toward more accessible and “markerless” motion labs, with future improvements possible (like better hand tracking or running on fewer cameras).

In short, the study demonstrates a reliable, clinic-ready way to turn everyday video into detailed, useful movement information that can help guide rehabilitation and improve patient care.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a consolidated list of concrete gaps and unresolved questions that future work could address to strengthen and extend the presented pipeline.

- Absent gold-standard validation: quantify per-joint kinematic accuracy against marker-based optical motion capture across activities and patient groups.

- Reliability not established: perform inter-session repeatability and test–retest reliability in both unimpaired and impaired populations, including sensitivity to clinically meaningful changes.

- Kinetics omitted: integrate contact/force modeling and evaluate joint torque and ground reaction force estimation accuracy versus force plates.

- Real-time feasibility unassessed: profile end-to-end latency, identify bottlenecks (implicit fitting, IK), and explore GPU acceleration/model compression to achieve near–real-time performance.

- Confidence estimation heuristic uncalibrated: validate the augmentation-based MeTRAbs confidence against true 2D/3D errors and compare alternative uncertainty estimators (e.g., MC dropout, ensembling).

- Lens distortion modeling limited: assess impact of using only the first radial distortion (k1) and evaluate higher-order distortion models on reconstruction accuracy.

- Rendering distortion workaround unvalidated: quantify projection/rendering errors introduced by pre-distorting mesh vertices (PyTorch3D limitation) and their effect on metrics.

- Calibration quality not quantified: measure intrinsic/extrinsic calibration repeatability and propagate calibration uncertainty into kinematic confidence intervals.

- Implicit trajectory model design unablated: systematically compare MLPs to splines, SIREN, neural ODEs, and piecewise polynomials; vary depth/width, positional encodings, and regularization.

- Computational scalability unknown: report runtime/memory for per-trial implicit fitting and bilevel IK; assess scalability to longer sequences, more markers, and fewer/more cameras.

- Limited reconstruction baselines: benchmark against bundle adjustment with temporal/skeletal priors, factor-graph smoothing, and probabilistic filters beyond robust triangulation.

- Joint-level analysis missing: provide per-joint noise/error and clinical acceptability thresholds; relate noise reductions to downstream clinical metrics.

- Pelvis/spine gains not quantified: measure improvements in pelvis orientation and hip/spine angles from dense markers under varying occlusion/camera coverage.

- Camera configuration guidelines absent: determine minimal camera number/placement for target accuracy in typical clinic spaces and corridors.

- Generalizability outside controlled rooms: evaluate robustness across sites, lighting, backgrounds, and different camera types (including low-cost RGB and RGB-D).

- Multi-person/occlusion robustness unmeasured: quantify failure rates in crowded scenes with caregivers/assistive devices and develop automated, robust subject tracking.

- Prosthesis-aware modeling lacking: create and validate biomechanical models and marker mappings for various prostheses (e.g., transfemoral, transtibial) and orthoses.

- Upper limb/hand limitations: fuse dense hand keypoints and adopt a hand/upper-limb musculoskeletal model; validate wrist/finger kinematics.

- Hyperparameter selection ad hoc: conduct cross-validated or Bayesian optimization of IK regularization, joint-limit penalties, and marker offset bounds; report sensitivity analyses.

- Model marker refinement risk: mitigate overfitting from dataset-wide mean offset updates with held-out validation across sites and release the refined marker set for replication.

- Monocular/minimal-view performance unknown: compare multi-view to monocular lifting (including using MeTRAbs 3D outputs) and characterize failure modes and accuracy trade-offs.

- Temporal gait metrics not evaluated: estimate cadence, stance/swing times, and double-support from kinematics alone and validate against instrumented walkway/IMUs.

- Task diversity limited: extend validation beyond gait to sit-to-stand, stairs, balance tasks, and upper-limb activities relevant to rehabilitation.

- Uncertainty in outputs not reported: propagate detection, calibration, and model uncertainties to produce confidence intervals for joint angles and gait parameters.

- Joint-limit formulation: systematically evaluate soft vs hard joint limits and data-driven joint-limit priors tailored to impaired populations.

- Physics constraints not leveraged: test whether adding dynamics/contact constraints improves kinematic plausibility and enables accurate kinetics from video alone.

- Frame-wise HPE limitation: compare sequence-based HPE (temporal models) to per-frame detection for biomechanical consistency improvements.

- Frame-rate dependence untested: assess effects of lower/higher frame rates on fast motions and angular velocity accuracy.

- Data/code availability unclear: specify and provide releases (including refined marker definitions and tuned hyperparameters) to enable independent replication.

- Clinical workflow and privacy: develop de-identification, failure handling, and integration guidelines for hospital deployment; evaluate user burden and throughput.

- Comparative benchmarks missing: perform head-to-head comparisons with OpenCap and commercial systems under identical conditions.

- Clothing/assistive device effects: quantify impact of loose garments, braces, walkers, and canes on keypoint detection and IK; develop mitigation strategies.

- Threshold choices not justified: tune Huber loss parameters, GC_5 threshold, and confidence cutoffs on validation data; analyze robustness to these settings.

- Torso/hip ground truth lacking: consider augmenting with a small number of IMUs to validate pelvis/torso orientations where optical ground truth is hard.

- End-to-end differentiability unimplemented: prototype an integrated, differentiable pipeline connecting perception, implicit trajectories, and IK (e.g., with GPU-native differentiable physics) and evaluate benefits.

Glossary

- Anthropomorphic prior: A regularization term that biases model scaling toward anatomically plausible human segment proportions. "including the anthropomorphic prior, ensuring the body segments have roughly consistent scaling"

- Bilevel optimization: An optimization framework where one problem is nested inside another (outer and inner loops), used here to jointly fit model parameters without a separate calibration trial. "We show that bilevel optimization"

- Calcaneus: The heel bone; its position is used to define heel contacts and spatial gait measures. "the location of the calcaneus bone"

- DART physics engine: The Dynamics and Robotics Toolkit; a physics engine used as a base for biomechanics extensions. "extends the DART physics engine"

- Direct linear transform: A linear method to triangulate 3D points from multiple 2D observations and known camera parameters. "the direct linear transform"

- Extrinsic and intrinsic calibration: Estimating camera pose (extrinsic) and internal parameters/distortion (intrinsic) for accurate multi-view reconstruction. "Extrinsic and intrinsic calibration was performed using the anipose library"

- Forward kinematic function: A function mapping joint angles and model parameters to 3D marker positions. "provides a forward kinematic function"

- Functional electrical stimulation: Electrical activation of nerves/muscles to assist or modulate movement. "functional electrical stimulation of the peroneal nerve to improve dorsiflexion"

- GaitRite walkway: An instrumented walkway that measures footfalls and spatiotemporal gait parameters. "a GaitRite walkway spanning the room diagonal"

- Geometric consistency (GC_5): A metric quantifying how closely reprojected model markers align with detected 2D keypoints within a pixel threshold. "We measured the geometric consistency"

- Ground reaction forces: Forces exerted by the ground on the body during stance, often estimated alongside joint torques. "joint torques and ground reaction forces"

- Huber loss: A robust loss function that is quadratic for small errors and linear for large errors to reduce outlier influence. "We use a Huber loss"

- Human pose estimation (HPE): Computer vision techniques that detect human joint/keypoint locations in images or video. "human pose estimation (HPE)"

- Implicit representation: Modeling trajectories as a continuous function of time (e.g., via a neural network) to enforce smoothness and anatomical consistency. "using an implicit representation to reconstruct smooth, anatomically constrained marker trajectories for IK,"

- Inverse kinematics (IK): Computing joint angles that best fit observed marker/keypoint trajectories given a biomechanical model. "inverse kinematic (IK) fits"

- Layer normalization: A neural network normalization technique applied across features within a layer to stabilize training. "each followed by a layer normalization"

- MeTRAbs-ACAE: A pose estimation approach trained across multiple datasets that outputs several keypoint formats, including dense biomechanical markers. "outputs all of these formats (MeTRAbs-ACAE)"

- Multi-layer perceptron (MLP): A feedforward neural network composed of multiple fully connected layers. "multi-layer perceptron (MLP)"

- Nimblephysics: A differentiable physics library (extending DART) tailored for biomechanics and IK optimization. "the nimblephysics library"

- Rajagopal model: A widely used full-body musculoskeletal model often adopted for biomechanics research. "the widely used Rajagopal model"

- Reprojection loss: A loss measuring the discrepancy between detected 2D keypoints and the 2D projections of reconstructed 3D points. "The reprojection loss is:"

- Robust triangulation: Triangulation that downweights inconsistent/outlier camera-keypoint observations to improve 3D reconstruction. "a robust triangulation algorithm"

- Scaling the skeleton: Estimating subject-specific body segment lengths and proportions to personalize the biomechanical model. "Scaling the skeleton before IK"

- Sinusoidal positional encoding: Encoding time (or position) with sinusoids to provide a neural network with periodic, multi-scale temporal features. "sinusoidal positional encoding"

- Soft joint limits: Regularized joint constraints that can be slightly exceeded to avoid optimization failure or implausible fits. "Using the soft, regularized joint limits allows the model to exceed the limits"

Practical Applications

Immediate Applications

The following applications can be deployed with the methods and performance reported in the paper (multi-camera setup, offline processing, inverse kinematics without a standing calibration trial, and dense keypoints via MeTRAbs-ACAE).

- Clinical gait analysis without markers for diverse rehab populations

- Description: Replace or augment traditional marker-based gait analysis with the presented markerless pipeline to quantify joint kinematics and spatial gait parameters in inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation (e.g., stroke, TBI, prosthesis users, knee OA). Demonstrated sensitivity to clinically meaningful changes (e.g., with AFO bracing or peroneal nerve FES) and spatial parameter errors of 8–13 mm.

- Sectors: Healthcare (rehabilitation medicine, physical therapy, orthopedics, neurology).

- Tools/Workflow: 8–10 PoE GigE cameras, checkerboard calibration, PosePipe + MeTRAbs-ACAE for dense MOVI keypoints, implicit trajectory reconstruction, nimblephysics IK with soft joint limits, auto-generated multi-view overlays for QA.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Multi-camera, calibrated, synchronized environment; adequate lighting; at least 3 concurrent views along walkway; offline compute; HIPAA/IRB-compliant video handling; staff trained to run calibration and basic QA.

- Rapid, in-clinic assessment of orthoses, prostheses, and assistive interventions

- Description: Use pre/post-condition comparisons (e.g., AFO tuning, prosthetic alignment, FES on/off) with averaged gait cycles to quantify intervention effects on joint angles and step metrics during standard clinical visits (<10 minutes per condition).

- Sectors: Healthcare; Medical devices (prosthetics/orthotics, neurostimulation).

- Tools/Workflow: Same pipeline; standardized condition labeling; automated reports that overlay condition averages and highlight differences; integration with existing GAITRite if available.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Consistent camera coverage across trial conditions; simple report templates; secure storage and retrieval of trial metadata.

- Objective outcome tracking in clinical research and trials

- Description: Use the pipeline as a sensitive outcome measure in rehab trials and longitudinal studies (e.g., post-stroke recovery trajectories, device efficacy) without standing calibration.

- Sectors: Academia; Clinical research organizations; Healthcare systems.

- Tools/Workflow: Batch processing of many sessions; version-controlled hyperparameters; standardized metrics (e.g., joint angle ranges, GC5, step/stride/width, joint-limit violations).

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Consistent setup across sessions and sites; documented analysis versions; power and sample-size planning informed by reported precision.

- Multi-view, markerless motion-capture stations for hospital networks

- Description: Deploy standardized camera kits (PoE for power/data/sync) to multiple clinics/wards to enable routine biomechanical assessments (bedside-adjacent rooms or therapy gyms).

- Sectors: Healthcare operations; Health IT.

- Tools/Workflow: Turnkey “gait station” kit; remote calibration checks; centralized or on-premises batch analysis; dashboard for scheduling and status.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Facilities support for mounting cameras and Ethernet; secure networking; SOPs for calibration cadence and drift checks.

- Quality assurance and benchmarking for commercial markerless systems

- Description: Use geometric consistency (GC5), residual marker errors, and step parameter accuracy as reference metrics to benchmark proprietary systems and HPE models in rehab populations.

- Sectors: Industry (motion capture vendors); Academia (method comparison).

- Tools/Workflow: Side-by-side acquisitions; shared evaluation scripts; overlay videos for qualitative review.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Access to proprietary outputs; consistent camera geometry; test datasets representing impaired gait.

- Curriculum and lab exercises for biomechanics education

- Description: Teaching modules where students run end-to-end analysis, inspect IK fits, and explore how keypoint density, trajectory representations, and joint-limit regularization affect results.

- Sectors: Academia (biomechanics, kinesiology, PT education).

- Tools/Workflow: Open-source pipeline; packaged example datasets; minimal install guides; Jupyter notebooks for parameter sweeps.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Workstation GPU/CPU resources; course-time allocation; instructor familiarity with basic computer vision.

- Ergonomics and occupational assessments in controlled test bays

- Description: Quantify joint kinematics and step parameters during task simulations (e.g., lifting, walking with loads) to identify risky postures and gait adaptations in a lab-like space.

- Sectors: Occupational health and safety; Ergonomics consulting.

- Tools/Workflow: Multi-camera bay; standard tasks; automated summaries with joint-limit exceedances and pose noise.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Controlled environment; reliable camera coverage with minimal occlusion; offline analysis acceptable.

- Sports biomechanics labs for gait and return-to-play screening

- Description: Apply pipeline to measure lower-limb kinematics and spatiotemporal metrics in running/walking screens where multi-camera coverage is feasible.

- Sectors: Sports performance; Sports medicine.

- Tools/Workflow: Camera ring around a short track or treadmill; standardized test protocols; comparative reports vs baseline.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Multi-view capture feasible; careful management of occlusions; profiles tailored to athletic gait speeds.

- Data governance and privacy policies at the institutional level

- Description: Implement immediate policies for secure storage, access control, and retention of identifiable video data used for clinical motion analysis.

- Sectors: Policy (institutional, hospital compliance).

- Tools/Workflow: HIPAA-compliant storage; consent language covering video capture; audit trails; role-based access.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Legal/compliance review; patient communication; institutional IT capacity.

Long-Term Applications

These applications require further research, scaling, model development, or engineering beyond the current study (e.g., real-time operation, fewer cameras, dynamics/kinetics, broader environments).

- Real-time biofeedback during therapy sessions

- Description: Deliver on-the-fly kinematic feedback (e.g., knee flexion targets, step width) to patients and therapists during walking or task practice.

- Sectors: Healthcare; Rehabilitation technology.

- Tools/Workflow: Streaming HPE; GPU-accelerated implicit reconstruction or alternative filters; low-latency IK; therapist dashboards.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Real-time implementations of trajectory reconstruction and IK; robust occlusion handling; UI design and clinical validation.

- Home-based markerless gait assessment with minimal cameras or monocular video

- Description: Extend methods to 1–2 cameras (or smartphone) for remote monitoring, tele-rehab, and fall-risk tracking in daily life.

- Sectors: Daily life; Telehealth; Eldercare.

- Tools/Workflow: Camera stands/mobile apps; model variants trained/validated for monocular or sparse multi-view; automated QC and failure detection.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Advances in multi-view-agnostic HPE, temporal models, or lifting; domain adaptation to cluttered home environments; privacy-preserving analytics.

- Full-body, hand-inclusive biomechanical tracking

- Description: Fuse dense body markers (MeTRAbs-ACAE) with hand-focused HPE to estimate wrist and finger kinematics with anatomically articulated hand models.

- Sectors: Healthcare (neuro/hand rehab); Robotics (dexterity modeling); Animation/VFX.

- Tools/Workflow: Multi-model fusion; expanded IK models (e.g., OpenSim hand); additional camera placement for hands.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Reliable dense hand keypoints; biomechanical hand models integrated with full-body IK; increased compute and calibration care.

- Physics-based dynamics and kinetics without force plates

- Description: Estimate joint torques and ground reaction forces using differentiable physics and learned ground-contact models to extend kinematics into kinetics.

- Sectors: Healthcare; Sports; Robotics; Medical devices.

- Tools/Workflow: Differentiable physics engines (nimblephysics, Brax); contact estimation; validation vs instrumented treadmills/force plates.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Accurate contact modeling; generalizable priors; cross-validated torque estimates; regulatory acceptance for clinical use.

- Automated clinical reporting and EMR integration

- Description: Generate structured, clinician-friendly summaries (norm-referenced kinematics, change-from-baseline, flags for atypical patterns) auto-pushed into EMRs.

- Sectors: Healthcare IT; Policy (documentation standards).

- Tools/Workflow: Report templates; HL7/FHIR integration; role-based review and sign-off; longitudinal dashboards.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: IT integration; standardization of metrics and reference ranges; clinical workflow redesign; governance approval.

- Standardization, validation frameworks, and reimbursement pathways

- Description: Develop consensus protocols, reference datasets (incl. impaired gait), and acceptance criteria for markerless systems; map outputs to CPT/HCPCS codes.

- Sectors: Policy; Professional societies; Payers.

- Tools/Workflow: Multi-site studies; open benchmarks with diverse pathologies; guidelines for calibration/QC and accuracy thresholds.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Stakeholder coordination; publication of comparative results; payer engagement.

- Scalable cloud services and SDKs for third-party products

- Description: Offer APIs/SDKs for uploading multi-view videos and returning kinematics/analytics, enabling device makers and app developers to embed gait analysis.

- Sectors: Software; Medical devices; Digital health.

- Tools/Workflow: Containerized pipeline; GPU cloud; privacy-preserving processing; developer documentation.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Data residency and compliance; latency and cost control; SLAs and support.

- Exoskeleton and robot control via human movement priors

- Description: Use accurate kinematic datasets from impaired and unimpaired gait to learn control policies or reference trajectories for assistive robots and exosuits.

- Sectors: Robotics; Rehabilitation engineering.

- Tools/Workflow: Dataset curation; sim-to-real pipelines; imitation learning or trajectory optimization seeded by measured IK.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Expanded datasets across tasks/speeds/devices; safety validation; controller robustness to variability.

- Footwear, orthotic, and implant design optimization

- Description: Integrate kinematic analytics into iterative design cycles (e.g., customizing AFO stiffness, shoe geometry) using virtual prototyping informed by patient-specific movement.

- Sectors: Medical devices; Footwear industry.

- Tools/Workflow: Parametric design tools linked to gait metrics; batch evaluation of candidate designs; human-in-the-loop testing.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Broader coverage of tasks (stairs, uneven terrain); linkage to kinetics for load modeling; IP and regulatory considerations.

- Public health and population mobility surveillance

- Description: Aggregate de-identified kinematic indicators to monitor functional mobility across populations (e.g., post-acute recovery trends).

- Sectors: Policy; Public health.

- Tools/Workflow: Privacy-preserving aggregation; bias audits; dashboards for health systems.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Large-scale deployment; strict privacy safeguards; interpretability and equity assessments.

- Cross-dataset training and domain adaptation for impaired movement

- Description: Expand multi-dataset HPE training with large rehab datasets and self-supervised video learning to further improve robustness and biomechanical consistency.

- Sectors: Academia; AI/ML research; Software tools.

- Tools/Workflow: Data pipelines with consented clinical video; biomechanical priors in self-supervised objectives; evaluation on standardized rehab benchmarks.

- Assumptions/Dependencies: Data access agreements; scalable compute; reproducible training recipes and open baselines.

Notes on feasibility across applications:

- Current pipeline is offline, multi-camera, and does not estimate kinetics; immediate uses should focus on kinematics and spatiotemporal parameters in controlled spaces.

- Accuracy and robustness hinge on dense keypoints (MeTRAbs-ACAE MOVI set), implicit trajectory reconstruction, and well-tuned IK with soft joint limits.

- Generalization to fewer cameras, real-time use, and unstructured environments will require additional algorithmic advances and validation.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.