Concentration on the Boolean hypercube via pathwise stochastic analysis

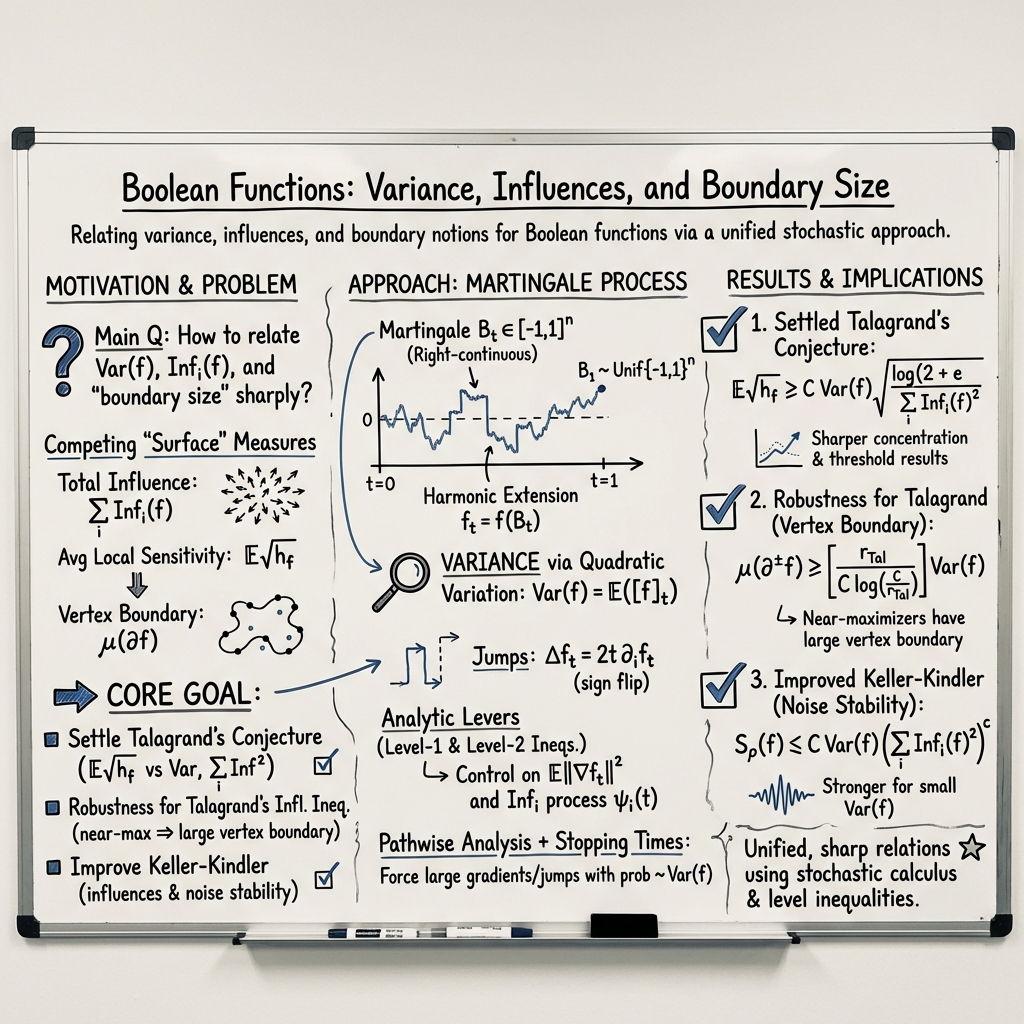

Abstract: We develop a new technique for proving concentration inequalities which relate between the variance and influences of Boolean functions. Using this technique, we 1. Settle a conjecture of Talagrand [Tal97] proving that $$\int_{\left{ -1,1\right} {n}}\sqrt{h_{f}\left(x\right)}dμ\geq C\cdot\mathrm{var}\left(f\right)\cdot\left(\log\left(\frac{1}{\sum\mathrm{Inf}{i}{2}\left(f\right)}\right)\right){1/2},$$ where $h{f}\left(x\right)$ is the number of edges at $x$ along which $f$ changes its value, and $\mathrm{Inf}{i}\left(f\right)$ is the influence of the $i$-th coordinate. 2. Strengthen several classical inequalities concerning the influences of a Boolean function, showing that near-maximizers must have large vertex boundaries. An inequality due to Talagrand states that for a Boolean function $f$, $\mathrm{var}\left(f\right)\leq C\sum{i=1}{n}\frac{\mathrm{Inf}{i}\left(f\right)}{1+\log\left(1/\mathrm{Inf}{i}\left(f\right)\right)}$. We give a lower bound for the size of the vertex boundary of functions saturating this inequality. As a corollary, we show that for sets that satisfy the edge-isoperimetric inequality or the Kahn-Kalai-Linial inequality up to a constant, a constant proportion of the mass is in the inner vertex boundary. 3. Improve a quantitative relation between influences and noise stability given by Keller and Kindler. Our proofs rely on techniques based on stochastic calculus, and bypass the use of hypercontractivity common to previous proofs.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

Big Picture: What Is This Paper About?

This paper is about how “fragile” or “stable” yes/no rules are when you change one little part of the input. The rules live on an n-dimensional cube made of 1s and −1s (think of n light switches, each either up or down). The authors find new and stronger ways to measure how much a rule can change when you flip one switch, and they invent a fresh way—using a kind of carefully designed random walk—to prove these results.

What Questions Do the Authors Ask?

They study Boolean functions, which are rules that take n bits (each −1 or 1) and output either −1 or 1. They focus on:

- How much does each switch matter? (This is called the “influence” of a switch.)

- How often does the rule change its answer when you move to a neighboring point of the cube? (This is called “sensitivity” or “boundary.”)

- How “spread out” is the power among the switches? (This shows up in sums of squared influences.)

- How stable is the rule if we add a little random noise to the input? (This is “noise stability.”)

The main questions:

- Can we connect how often a function changes (its sensitivity/boundary) with how much its output varies overall (its variance) and with how its influences are distributed?

- Can we strengthen famous results (like those of Talagrand and KKL) and say that any function nearly reaching the best possible bound must have many inputs on its boundary?

- Can we improve how influences control noise stability?

How Do They Study It? (Methods in Simple Terms)

Instead of using heavy algebraic tools that previous proofs relied on, the authors build a “movie” of how a random input is created over time:

- Imagine starting at the “center” (all coordinates at 0) and then, as time goes from 0 to 1, each coordinate gradually commits to either −1 or 1. At the end (time 1), you’ve generated a perfectly uniform random corner of the cube. Along the way, sometimes a coordinate suddenly flips direction—these are “jumps.”

- As this happens, you watch the function’s value through time: does it stay steady or does it jump a lot? You also watch how sensitive the function is at each moment (like checking how steep a hill is as you walk).

- This time-evolving picture is designed to be a “fair game” (a martingale): your best prediction now equals your best prediction later. That lets them use powerful math rules about fair games—like how total “jumpiness” relates to overall variability (variance).

Two built-in “speed limits” (called Level-1 and Level-2 inequalities) control how fast the function’s “slope” and “curvature” can grow as you approach time 1. Think of them as saying: if the function’s influences are tiny or spread thinly, then most of the real action (big changes) must happen very late in the process. This insight lets the authors pin down when and how the function must jump.

What Did They Find, and Why Does It Matter?

Here are the core results, in everyday language:

- They confirm and strengthen a conjecture by Talagrand: The average “edge-sensitive” behavior of the function (roughly, the typical number of neighboring inputs that would flip the answer) must be large if: 1) the function’s output varies a lot overall (high variance), and 2) the function spreads its influence thinly across many switches (small sum of squared influences).

In short: if no single switch matters much, the function must be “edgy” in many places. This unifies two classic viewpoints—total influence (good for Tribe-like functions) and average sensitivity (good for Majority-like functions)—into one stronger statement.

- They prove a strengthened version of Talagrand’s inequality with a clean byproduct: If a function nearly maximizes the classical bound relating variance and influences, then a big chunk of inputs lie right on the boundary—meaning, flipping a single bit would change the output. This is a “robustness” or “stability” statement: near-best functions must look boundary-rich.

- They apply this robustness in two important directions:

- Near the edge-isoperimetric inequality (the sharpest possible edge-boundary condition on the cube), a constant fraction of the set must lie in the inner vertex boundary. Intuition: if you almost have the smallest edge boundary possible for your size, then many points are just one flip away from leaving the set.

- Near the KKL inequality (which says at least one variable must have nontrivial influence), if all influences are about as small as allowed, then again a constant fraction of inputs sit on the boundary. So functions that are “barely stable enough” must be boundary-heavy.

- They improve a known link between influences and noise stability: Noise stability measures how often the output stays the same after lightly randomizing the input. They show a tighter bound that gets stronger when the function’s variance is small. Translation: if your function doesn’t vary much overall and its influence is spread thin, then it can’t be very noise-stable.

Why this matters:

- These results sharpen our understanding of how complex yes/no rules behave on large, high-dimensional spaces. That’s useful in theoretical computer science (learning, communication, approximation), probability, and even social dynamics (e.g., majority voting) and physics (phase transitions). Stronger, more flexible inequalities give better tools across these areas.

What’s New About Their Approach?

The fresh idea is the “pathwise” or “movie-through-time” method:

- Instead of applying a global smoothing tool (hypercontractivity) as in earlier proofs, they build a step-by-step random process that ends at a uniformly random input and analyze the function’s behavior along the way.

- Because the process is a fair game (martingale), they can use optional stopping (you can pause the movie at smart times) and connect the total jump size to the final variability. This path-by-path control tells you not just that the average is big, but that it’s big on a significant set of paths—crucial for boundary and robustness results.

- The two “speed limits” (Level-1 and Level-2 inequalities) act like real-time constraints on how fast sensitivity can grow, which pinpoints where the function must be boundary-heavy.

What Could This Influence Next?

- Stronger, cleaner concentration and robustness results can sharpen algorithms in learning theory (deciding which variables matter), inform lower bounds (how hard certain tasks really are), and deepen our understanding of thresholds in networks and physics models.

- The new pathwise technique may inspire similar proofs in other settings (like Gaussian space), offering a flexible toolkit beyond traditional methods.

In short: the paper settles a long-standing conjecture, strengthens classic bounds, and introduces an elegant, intuitive method that could power future advances across math and computer science.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a single list of concrete gaps and open directions left unresolved by the paper, aimed to guide future research:

- Optimal constants and tightness: Determine the best possible universal constants (e.g., in Theorems 1, 2, and 5), and identify extremal or near-extremal Boolean functions (beyond majority and Tribes) that saturate the new bounds. Establish matching lower bounds to certify the sharpness of the logarithmic and power dependencies.

- Explicit and interpretable construction of the auxiliary function g_f: Theorem 2 guarantees the existence of a function g_f with E[g_f2] ≤ 2 Var(f) that certifies the strengthened Talagrand bound, but does not provide an explicit formula or characterization. Develop a concrete, canonical choice (e.g., in terms of stopping times, local gradients, or structural features of f), and analyze its regularity and support.

- Extension beyond monotone functions in level inequalities: The Level-2 inequality (used critically in the pathwise proofs) is stated for harmonic extensions of monotone functions. Establish analogous bounds for general (non-monotone) Boolean functions or quantify the additional error terms needed, and assess how such extensions impact the main concentration inequalities.

- Dependence on the noise parameter in the improved Keller–Kindler bound: Theorem 5 improves Keller–Kindler by inserting Var(f), but the role and range of the noise parameter (ρ) are not fully specified. Derive explicit ρ-dependent constants and exponents, determine whether the bound can be uniform over ρ, and assess sharpness as ρ→0 or ρ→1.

- Generalization to biased product measures (μ_p): Many central statements are given under the uniform measure on the cube; while biased Fourier tools are invoked in the appendix, the main theorems are not stated for μ_p. Extend Theorems 1–4 to biased hypercubes, clarify the correct dependence on p, and adapt the pathwise martingale construction accordingly.

- Structural robustness under O(1)-slack: The paper proves that near-maximizers (for Talagrand’s inequality, isoperimetry, and KKL) have large vertex boundaries, but stops short of structural classification. Develop robust “stability” theorems under constant-factor slack (not just 1+ε regimes), e.g., closeness (in symmetric difference or Hamming distance) to subcubes or juntas, and quantify distances as functions of the slack.

- Combined boundary inequalities: The strengthened Talagrand bound involves E[√{h_f}] and influences, while robustness results involve μ(∂f). Derive unified inequalities that explicitly combine edge boundary, vertex boundary, sensitivity distributions (h_f), and influence profiles in a single bound, and identify regimes where each boundary notion dominates.

- Extension to non-Boolean outputs: The pathwise technique is developed mainly for f: {−1,1}n → {−1,1} (and occasionally bounded reals via harmonic extensions). Generalize the core results (and level inequalities) to real-valued, multi-valued, or threshold functions, and quantify how ranges beyond {−1,1} affect variance–influence–boundary tradeoffs.

- Pathwise method reach and limitations: Identify which classical hypercontractive or log-Sobolev-type inequalities can be reproved or strengthened via the martingale B_t approach. Clarify limitations (e.g., settings where hypercontractivity seems indispensable) and explore whether stopping-time arguments yield new tail bounds or reverse inequalities.

- Noise models beyond independent bit flips: The noise stability bound focuses on the standard product noise. Extend to more general Markovian noise (e.g., dependent coordinates, graph-based dynamics, or non-product kernels), derive influence–stability relations in those models, and characterize when the pathwise analysis adapts.

- Dimension-sensitive refinements: Although constants are “universal”, study finite-n corrections and regimes (small n, low variance, ultra-sparse influences) where current bounds may be vacuous or suboptimal. Provide refined inequalities with explicit n-dependence or second-order terms.

- Time-scale decomposition and tail behavior: The pathwise framework yields an integral representation of Var(f) over time scales. Leverage this to produce multi-scale decompositions (e.g., how much variance accumulates near t≈1), and to derive high-probability tail bounds for quadratic variation and for f(B_t) itself.

- Algorithmic and empirical implications: Investigate whether the martingale B_t can be used computationally to estimate influences, sensitivity, or vertex boundary from samples. Develop algorithms that mimic the pathwise analysis and quantify sample complexity, runtime, and robustness to noise.

- Extension to other discrete geometries: Adapt the pathwise method to slices of the cube (Johnson graphs), the symmetric group, or general product spaces with constraints, and derive analogues of KKL/Talagrand/isoperimetric/stability inequalities in those settings.

- Clarify and optimize Level-1/Level-2 constants: The lemmas invoke general constants (L and C(t)). Tighten these constants, establish their optimal forms, and assess the impact on the main theorems’ constants and exponents, especially in boundary regimes where g(x) is small or t→1.

Glossary

- Boolean Fourier-analysis: The study of Boolean functions using Fourier expansions on the hypercube. Example: "uses classical Boolean Fourier-analysis only sparingly"

- Boolean hypercube: The discrete set of n-bit vectors with entries in {-1,1}, often denoted {−1,1}n. Example: "Concentration on the Boolean hypercube via pathwise stochastic analysis"

- Brownian motion: A continuous-time stochastic process with independent Gaussian increments and continuous paths. Example: "Let W_{s} be a standard Brownian motion."

- Edge-isoperimetric inequality: A bound giving the minimal number of edges leaving a subset of the hypercube for a given size of the subset. Example: "The edge-isoperimetric inequality \cite[section 3]{sergiu_a_note_on_the_edges_of_the_n_cube} states that"

- Filtration: An increasing family of sigma-algebras representing the information revealed up to each time in a stochastic process. Example: "measurable with respect to the filtration generated by \left{ B_{s}\right} _{0\leq s<t}"

- Fourier coefficients: The coefficients in the expansion of a Boolean function in the orthonormal basis of parity functions on the hypercube. Example: "the harmonic coefficients (also known as Fourier coefficients) \hat{f}\left(S\right) are given by"

- Fourier mass: The total squared weight of Fourier coefficients on specified levels (e.g., level-1 mass). Example: "implying that the Fourier mass on the first level is proportional to a power of the variance."

- Gaussian space: A probability space equipped with a Gaussian measure (e.g., \mathbb{R}n with standard normal distribution). Example: "an elementary proof of the isoperimetric inequality on Gaussian space."

- Harmonic extension: The multilinear polynomial extension of a Boolean function from {−1,1}n to [-1,1]n (or \mathbb{R}n). Example: "We call this the harmonic extension, and denote it also by ."

- Hessian: The matrix of all second-order partial derivatives of a function. Example: "where is the Hessian of "

- Hilbert-Schmidt norm: The Frobenius norm of a matrix, the square root of the sum of squares of its entries. Example: "and $\norm X_{HS}=\sqrt{\sum_{i,j}X_{ij}^{2}$ is the Hilbert-Schmidt norm of a matrix."

- Hypercontractive principle: An inequality controlling how norms behave under noise operators; central in analysis of Boolean functions. Example: "Talagrand's original proof of Theorem \ref{thm:talagrands_inequality}, as well as later proofs (see e.g \cite{cordero_ledoux_hypercontractive_measures}), all rely on the hypercontractive principle."

- Influence (of a Boolean function): The probability that flipping a particular bit changes the value of the Boolean function. Example: "The influence of a Boolean function in direction is defined as"

- Inner vertex boundary: The set of vertices with function value 1 that have at least one neighbor with value −1. Example: "It is the disjoint union of the inner vertex boundary,"

- Isoperimetric inequality: A general principle relating the “surface area” (boundary) and “volume” (measure) of sets; on the cube or Gaussian space, it gives sharp boundary-size lower bounds. Example: "It is natural to ask about the robustness of the isoperimetric inequality:"

- Kahn–Kalai–Linial (KKL) inequality: A fundamental result giving a logarithmic-strengthened variance bound via influences, and guaranteeing a variable with large influence. Example: "The KKL inequality is tight for the Tribes function,"

- Level-1 inequality: A bound relating first-level Fourier weight (or gradient size) to the mean of a Boolean function. Example: "two well-known inequalities - called the Level-1 and Level-2 inequalities -"

- Level-2 inequality: A bound relating second-level Fourier weight (or Hessian size) to first-level quantities. Example: "two well-known inequalities - called the Level-1 and Level-2 inequalities -"

- Martingale: A stochastic process whose conditional expectation at any future time equals its current value given the past. Example: "the process is a martingale."

- Noise sensitivity: The tendency of a Boolean function’s value to decorrelate under small random perturbations of the input. Example: "The relation between influences and noise sensitivity was first established in \cite{benjamini_kalai_schramm_noise_sensitivity},"

- Noise stability: The covariance or correlation of a Boolean function under a correlated (noisy) copy of its input. Example: "Let be the noise stability of , i.e"

- Optional stopping theorem: A result stating that, under conditions, a martingale stopped at a stopping time preserves its expectation. Example: "X_{t} is a martingale due to the optional stopping theorem."

- Outer vertex boundary: The set of vertices with function value −1 that have at least one neighbor with value 1. Example: "and the outer vertex boundary,"

- Piecewise-smooth jump process: A process that is smooth between random jump times and undergoes discrete jumps at those times. Example: "A process is said to be a piecewise-smooth jump process with rate "

- Poisson point process: A random counting process with independent increments where counts over intervals are Poisson distributed with mean given by the integrated rate. Example: "A Poisson point process with rate is an integer-valued process"

- Poincaré inequality: An inequality bounding the variance of a function by a Dirichlet form; on the cube it bounds variance by total influence. Example: "The Poincaré inequality gives an immediate relation between the aforementioned quantities, namely,"

- Quadratic variation: A process measuring the accumulated sum of squared increments; for jump processes equals the sum of squared jump sizes. Example: "An important notion in the analysis of stochastic processes is quadratic variation."

- Sensitivity (of a Boolean function): The number of coordinates at which flipping that coordinate changes the function value at a given input. Example: "is the sensitivity of at point ."

- Stopping times: Random times determined by the past of a stochastic process, at which one may stop the process. Example: "Consider the family of stopping times"

- Subgaussian: Having tail behavior dominated by (or comparable to) that of a Gaussian random variable. Example: "the fact that is subgaussian;"

- Submartingale: A stochastic process whose conditional expectation at a future time is at least its current value given the past. Example: "Since $\norm{ f\left(B_{1}\right)}_{2}^{2p}$ is a submartingale,"

- Symmetrification: A technique that modifies a process or function to enforce symmetry, often simplifying analysis. Example: "using a symmetrification of (Proposition \ref{prop:using_the_event_E})."

- Tensorization: A principle that lifts one-dimensional functional inequalities to product spaces by factorization. Example: "which implies Bobkov's inequality via tensorization,"

- Vertex boundary: The set of vertices that have at least one neighbor where the Boolean function takes the opposite value. Example: "Another notion of surface-area is the vertex boundary of , defined as"

Practical Applications

Overview

This paper introduces a pathwise, stochastic-calculus-based technique to prove and strengthen concentration inequalities for Boolean functions on the hypercube. It settles Talagrand’s conjecture by relating variance to sensitivity and squared influences; provides robustness results that force large vertex boundaries near tightness of Talagrand/KKL/isoperimetric inequalities; and improves quantitative relations between influences and noise stability. A central innovation is a martingale jump process on the continuous hypercube that turns variance, influences, and sensitivity into integrals of derivatives along sample paths, enabling optional stopping, conditioning, and time-localized analysis.

Below are practical applications that leverage these findings and methods. Each item includes sectors, actionable use cases, potential tools/workflows, and feasibility assumptions.

Immediate Applications

The following can be deployed now, relying on existing Boolean models or approximations and Monte Carlo estimation of influences/sensitivity.

- Robustness auditing for binary decision systems

- Sector: software, robotics, safety-critical systems, healthcare decision support

- Use: Diagnose fragility in rule-based or Boolean-logic components by lower-bounding the proportion of inputs on the vertex boundary (where single-bit flips change outputs). If a system’s rules nearly saturate KKL or edge-isoperimetric bounds, expect many “knife-edge” cases; prioritize robustness hardening and test coverage there.

- Tools/workflows:

- Implement the paper’s martingale sampler B_t to estimate Var(f), ΣInf_i(f), ΣInf_i(f)2, and E[√h_f].

- Compute r_Tal = Var(f)/Σ_i Inf_i(f)/(1+log(1/Inf_i(f))) to trigger boundary alerts via Theorem 1.5 (large inner/outer vertex boundaries).

- Integrate into CI pipelines to flag high-boundary modules and auto-generate edge-case tests near boundaries.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Access to Boolean function or a surrogate; bit independence approximations; estimates via Monte Carlo; monotonicity simplifies bounds.

- Influence-guided feature testing and fuzzing

- Sector: software QA, ML systems with Boolean gates (feature flags, safety interlocks), cybersecurity

- Use: Use influence profiles to focus fuzzing and adversarial testing on high-impact bits and threshold regions where small perturbations flip outcomes.

- Tools/workflows:

- Influence Analyzer: estimate Inf_i via sampling partial derivatives; rank bits and define fuzzing budgets proportional to influences.

- Boundary Explorer: target regions with high E[√h_f] or large ∥∇f_t∥_2 via the pathwise process to generate minimal flipping inputs.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Stable mapping from real inputs to Boolean bits; ability to sample; harmonic extension supports gradient-like estimators.

- Noise sensitivity monitoring for decision policies

- Sector: social networks (majority dynamics), A/B testing and experimentation platforms, statistical physics (percolation simulations)

- Use: Measure susceptibility to random perturbations (channel noise, randomized interventions) via improved noise-stability bounds S_ρ(f) ≤ C Var(f) (ΣInf_i2)c. Prioritize policies with lower ΣInf_i2 to reduce volatility and improve reproducibility.

- Tools/workflows:

- Noise Stability Monitor: estimate ΣInf_i2 and Var(f) to bound S_ρ(f); annotate experiments with predicted sensitivity.

- Early warning: flag features likely to exhibit sharp thresholds or volatile outcomes.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Appropriateness of the paper’s product noise model; Monte Carlo estimates; constants are universal but not optimized.

- Data-driven threshold diagnostics in experiments and AB testing

- Sector: product analytics, marketing experimentation, online platforms

- Use: Detect impending sharp thresholds tied to concentration inequalities; proactively adjust ramp-up strategies or guardrails to avoid brittle behavior.

- Tools/workflows:

- Compute ΣInf_i and ΣInf_i2 for Boolean outcome proxies; if ΣInf_i2 is small and Var(f) moderate, expect late-time variance accumulation (per pathwise Level-2 analysis), plan staged rollouts.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Boolean proxies for outcomes; independent bit model approximations.

- Educational and research tooling

- Sector: academia, education

- Use: Teach concentration/influence/noise stability with interactive visualizations of the B_t process and quadratic variation links to variance.

- Tools/workflows:

- Open-source “Boolean Martingale Lab”: simulate sample paths, track jumps, visualize how variance accumulates near t=1, and demonstrate optional stopping.

- Assumptions/dependencies: None beyond standard numerical tooling.

- Risk and compliance triggers sensitivity analysis

- Sector: finance (binary risk flags, compliance triggers), operations (alerting systems)

- Use: Evaluate how sensitive binary triggers are to single-signal flips; reduce unnecessary volatility by redesigning logic with smaller vertex boundary mass or redistributing influences.

- Tools/workflows:

- Influence/Bdry Audit: estimate Inf_i and μ(∂f); recommend logic refactors (e.g., redundancy or voting) to lower sensitivity.

- Assumptions/dependencies: Decision logic expressible as Boolean or approximated; stochastic independence approximations.

Long-Term Applications

These require adaptation, scaling, or domain-specific modeling beyond the paper’s immediate setting (e.g., correlated inputs, non-binary variables, optimized constants, large-scale compute).

- Explainable and robust AI via influence geometry

- Sector: ML/AI (neuro-symbolic models, decision trees, rule-based systems)

- Use: Build explainability modules that report influence distributions, boundary mass, and predicted noise sensitivity for models with Boolean substructures; guide model compression and safety checks.

- Tools/products:

- Influence Geometry Toolkit: unify variance–influence–boundary diagnostics; incorporate pathwise estimators and stopping-time strategies for attribution.

- Dependencies: Extending to non-Boolean features and correlated inputs; integrating with modern ML stacks; efficient large-n estimation.

- Fault-tolerant logic design for cyber-physical systems

- Sector: robotics, autonomous vehicles, industrial control, energy grids

- Use: Design control logic with minimized vertex boundary (fewer inputs near single-bit flip points) to improve robustness against sensor noise and bit errors; adapt redundancy or majority schemes informed by Talagrand/KKL bounds.

- Tools/workflows:

- Robust Logic Synthesizer: optimize Boolean controllers to reduce ΣInf_i and μ(∂f) while meeting performance constraints; simulate with the B_t framework to predict late-time sensitivity accumulation.

- Dependencies: Mapping physical noise models to the paper’s product noise; multi-signal correlations; certification requirements.

- Network reliability and epidemic/contagion policy design

- Sector: energy (grid reliability), public health (epidemic interventions), social networks (misinformation spread)

- Use: Use improved quantitative noise sensitivity and vertex boundary insights to anticipate phase transitions and sharp thresholds; design policies that reduce individual bit influence to delay or blunt cascades.

- Tools/workflows:

- Threshold Management Planner: identify high-influence nodes/edges, restructure interventions to diversify influence and reduce ΣInf_i2; monitor late-stage variance accumulation.

- Dependencies: Translating Boolean hypercube models to network contagion with dependencies; domain-specific calibration; ethical and policy constraints.

- Privacy-preserving and robust decision rule engineering

- Sector: privacy, fairness, policy governance

- Use: Craft decision rules with controlled influences and boundary mass to lessen sensitivity to single attributes, potentially reducing disparate impact and increasing stability under randomization.

- Tools/workflows:

- Fairness via Influence Control: regularize rule learning with penalties on ΣInf_i and ΣInf_i2, using theoretical bounds to trade off variance and sensitivity.

- Dependencies: Legal and regulatory alignment; extending results to biased, correlated, or continuous features.

- Program analysis and synthesis tools

- Sector: software engineering

- Use: Static/dynamic analyzers that automatically extract Boolean decision logic, estimate influence/sensitivity, and refactor code to reduce brittle thresholds; integrate optional stopping-based testing heuristics.

- Tools/products:

- “Threshold Robustness Scanner” and “Noise Stability Monitor” integrated into IDEs/CI.

- Dependencies: Scalable symbolic execution; efficient Monte Carlo on large decision spaces; developer adoption.

- Advanced learning algorithms for monotone/junta functions

- Sector: machine learning theory and practice

- Use: Exploit the improved Talagrand bounds and pathwise Level-1/Level-2 inequalities to tighten sample complexity and stopping rules in learning monotone/junta functions; design algorithms that adaptively focus on high-variance late-time regions indicated by the B_t process.

- Tools/workflows:

- Adaptive Influence Learner: employs stopping-time strategies to concentrate samples where ∥∇f_t∥ grows near t→1.

- Dependencies: Algorithmic development and proofs; integration with noisy, non-product distributions.

Key Assumptions and Dependencies

- Boolean modeling: Many applications assume decision rules can be represented as or approximated by Boolean functions; monotonicity simplifies bounds.

- Independence and product measures: The martingale and bounds are derived under product (independent bits) assumptions; correlated inputs require extensions.

- Access and estimability: Practical use requires the ability to sample inputs, evaluate f, and estimate influences/sensitivity via harmonic extension or Monte Carlo.

- Constants and tightness: Bounds use universal constants; domain-specific optimization may be needed for practical thresholds.

- Scalability: Estimating ΣInf_i, ΣInf_i2, E[√h_f], and variance for large n may be computationally intensive; approximate or randomized methods are essential.

These applications translate deep theoretical advances into actionable diagnostics and design principles for systems whose behavior is governed by thresholded, rule-based, or Boolean-like decisions, while the pathwise method enables new tooling based on sampling and stopping-time analysis.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.