ACTS in Need: Automatic Configuration Tuning with Scalability Guarantees

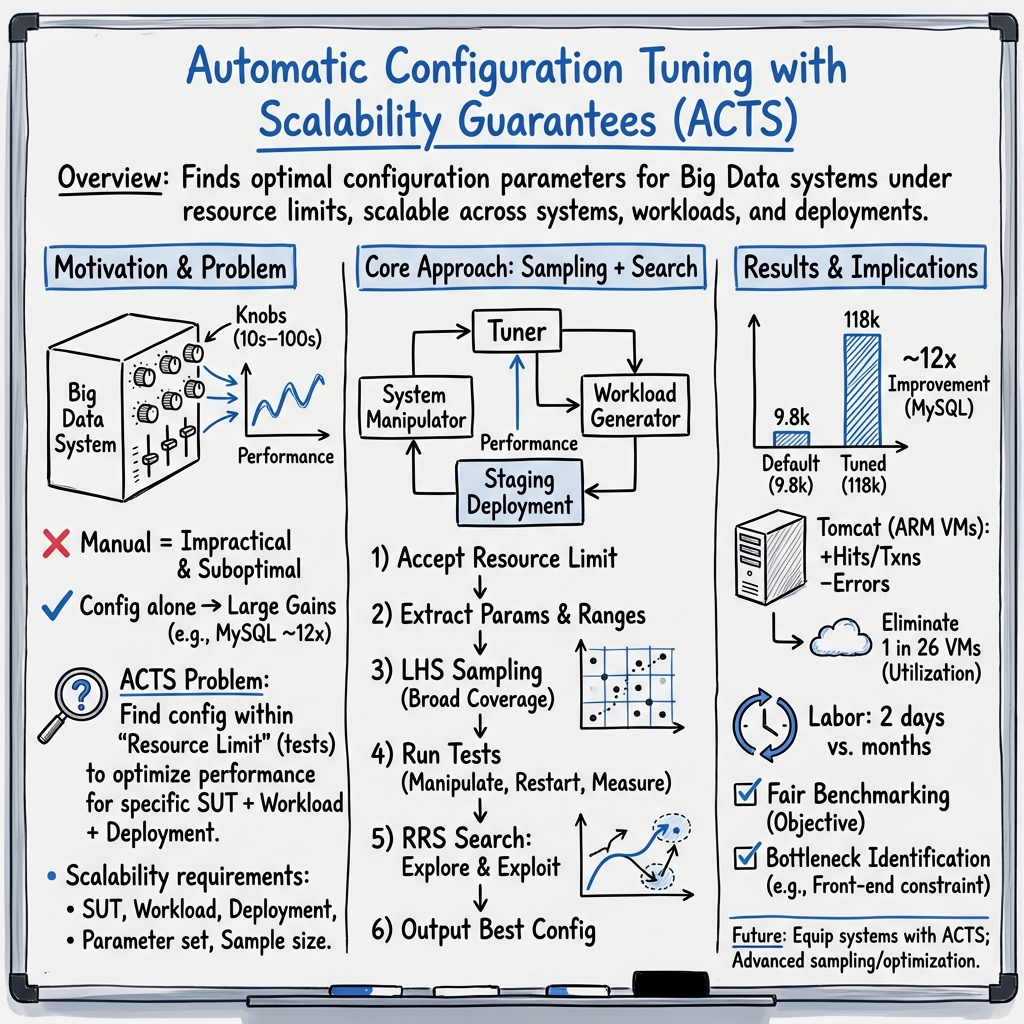

Abstract: To support the variety of Big Data use cases, many Big Data related systems expose a large number of user-specifiable configuration parameters. Highlighted in our experiments, a MySQL deployment with well-tuned configuration parameters achieves a peak throughput as 12 times much as one with the default setting. However, finding the best setting for the tens or hundreds of configuration parameters is mission impossible for ordinary users. Worse still, many Big Data applications require the support of multiple systems co-deployed in the same cluster. As these co-deployed systems can interact to affect the overall performance, they must be tuned together. Automatic configuration tuning with scalability guarantees (ACTS) is in need to help system users. Solutions to ACTS must scale to various systems, workloads, deployments, parameters and resource limits. Proposing and implementing an ACTS solution, we demonstrate that ACTS can benefit users not only in improving system performance and resource utilization, but also in saving costs and enabling fairer benchmarking.

Paper Prompts

Sign up for free to create and run prompts on this paper using GPT-5.

Top Community Prompts

Explain it Like I'm 14

A Simple Explanation of “ACTS in Need: Automatic Configuration Tuning with Scalability Guarantees”

Overview: What’s this paper about?

This paper talks about a way to automatically tune the “settings” of big computer systems so they run faster and use fewer resources. Think of these settings like the many sliders and switches in a video game that change graphics, sound, and controls. In big data systems (like MySQL, Hadoop, Spark, or Tomcat), there are hundreds of such “knobs.” Picking the best combination can make the system much faster—sometimes about 11 times faster—but doing it by hand is too hard for most people. The authors propose ACTS, a method to tune these settings automatically and reliably in many different situations.

Goals: What questions are the authors trying to answer?

The authors want to know if we can build an automatic tuning system that:

- Works for different kinds of systems (databases, web servers, data processing engines).

- Adapts to different workloads (the kind of tasks the system is doing, like many reads vs. mixed reads and writes).

- Handles different deployment environments (single machines vs. clusters, different hardware, and co-running software like Java).

- Tunes lots of settings (sometimes hundreds) without oversimplifying.

- Still finds good results even when it can only run a limited number of tests (because tests can be slow and expensive), and gets better if it’s allowed to run more.

In short, they want automatic tuning that “scales” across systems, workloads, environments, parameter sets, and the number of tests.

Methods: How did they approach the problem?

The authors designed a flexible setup (an “architecture”) with three parts:

- A tuner: the brain that decides which settings to try next.

- A system manipulator: the hands that apply new settings to the system and restart it if needed.

- A workload generator: the engine that runs real or realistic tasks to measure performance.

They run these tuning tests in a “staging environment,” which is a safe copy of the real system. It has the same hardware and software as production but won’t disrupt real users. This way, they can measure actual performance without risking live systems.

To pick which settings to try, they use two ideas:

- Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS): Imagine each setting’s range as a line divided into equal segments. LHS picks samples so that, across all settings, it covers the space evenly. It’s like ensuring you taste every “slice” of each ingredient when experimenting with recipes, rather than accidentally sampling the same few combinations.

- Recursive Random Search (RRS): This is like looking for the highest hill in a huge, bumpy landscape. First, you wander around randomly to find a promising spot (exploration). Then you search nearby to climb higher (exploitation). If you stop getting higher, you jump to a new area and try again. This helps avoid getting stuck on a small hill when a taller one exists somewhere else.

They chose LHS because it covers the setting space well even with few samples, and RRS because it keeps improving results and doesn’t get stuck easily.

Findings: What did they discover, and why does it matter?

- Huge speedups are possible. For MySQL (a popular database), tuning the settings increased throughput from about 9,815 operations per second to about 118,184—roughly 11 times faster—without changing the code, just the settings.

- Small boosts matter at scale. For Tomcat (a web server), tuning gave improvements of around 4–12% on different metrics. That may seem modest, but in a large cloud deployment, even a few percent can let you run fewer virtual machines. The authors estimate you could remove about 1 out of every 26 machines for the same traffic.

- Saves a lot of time and money. Manual tuning can take months of human effort and still miss better settings. Their automatic method found better results in just a couple of days.

- Fairer comparisons between systems. When researchers compare systems (benchmarking), results can be misleading if the systems aren’t properly tuned. ACTS makes the tuning process more objective and consistent, so comparisons are more trustworthy.

- Finds bottlenecks. In systems that work together (for example, a front-end cache plus a database), ACTS helps figure out which part is slowing things down. You can tune each piece and the combination to see where performance gets stuck, which points to the real problem.

Implications: Why is this important for the future?

Computer systems are getting more complex, with more knobs to turn and more ways those knobs interact with hardware, workloads, and other software. Doing this by hand is often impractical. ACTS shows that automatic tuning is not only possible, but powerful and cost-effective. It can:

- Make systems faster without changing the code.

- Reduce cloud costs by using fewer machines for the same job.

- Help teams benchmark fairly and avoid misleading claims.

- Guide engineers to the true causes of slowdowns.

The authors believe future systems should include automatic tuning as a built-in feature. Their approach is a first step and opens up many research opportunities to make automatic configuration tuning even better.

Knowledge Gaps

Knowledge gaps, limitations, and open questions

Below is a concise list of what remains missing, uncertain, or left unexplored in the paper, framed to guide future research:

- Lack of formal guarantees: no theoretical analysis of convergence, optimality, or sample complexity for LHS+RRS in high-dimensional, mixed-type (boolean, categorical, numeric) configuration spaces.

- Limited evaluation scope: absence of systematic, large-scale experiments across diverse SUTs, workloads, deployments, and knob counts (tens to hundreds) to validate scalability claims.

- Noise and non-determinism: no treatment of measurement noise, performance variability, run-to-run randomness, or statistical confidence (e.g., repeated trials, confidence intervals, robust optimization).

- Mixed-type and conditional parameters: incomplete methodology for encoding categorical/enumeration knobs, handling hierarchical/conditional dependencies, and enforcing hard constraints/invalid combinations during search.

- High-dimensionality effects: no empirical or theoretical study of how search effectiveness and coverage degrade as dimensionality increases (curse of dimensionality), or strategies like hierarchical/active subspace selection.

- Joint tuning across co-deployed systems: no algorithmic framework for multi-system joint optimization capturing cross-system interactions, shared-resource constraints, and coordinated search.

- Multi-objective optimization: focus on throughput; no support for balancing latency (including tail), resource consumption, cost, reliability, or SLA constraints (e.g., constrained or Pareto optimization).

- Adaptive resource budgeting: no policy for allocating the number of tests adaptively (early stopping, budget reallocation), or guidance on choosing m (samples) under varying workload durations and stability.

- Online/continuous tuning: reliance on offline staging; no strategy for online adaptation to workload drift, diurnal patterns, data evolution, or system updates, including safe deployment (canary/A-B) in production.

- Staging–production fidelity: unexamined risk that staging differs from production (hardware, contention, multi-tenancy); missing methods to detect drift and correct for domain mismatch or to transfer configurations safely.

- Failure and safety handling: no plan for invalid/crashing configurations, rollback, safe exploration under system health constraints, or guarding against catastrophic performance regressions.

- Parameter range inference: unspecified process for discovering realistic/safe parameter bounds automatically; risk of too narrow or overly broad ranges impacting search outcomes.

- Experiment scheduling: no optimization of test order given restart requirements, warm-up times, heterogeneous test durations, caching effects, or minimizing time-to-result.

- Workload representativeness: no framework for defining, generating, or validating workload coverage; lack of workload taxonomies or workload similarity metrics to guide tuning transfer.

- Sample efficiency benchmarking: absence of head-to-head comparisons with alternative optimizers (e.g., Bayesian optimization/SMAC/BOHB, CMA-ES, genetic algorithms, bandits) under tight sample budgets.

- Model-assisted search: no exploration of surrogate modeling, meta-learning, or transfer learning to leverage historical data while respecting deployment specificity.

- Bottleneck attribution: anecdotal bottleneck diagnosis; no systematic method (e.g., sensitivity analysis, Shapley values, causal inference) to attribute performance limits to specific systems or interactions.

- Metrics and observability: undefined metrics beyond throughput (e.g., latency percentiles, queueing, resource saturation); no standardized instrumentation, outlier filtering, or monitoring integration.

- Reproducibility and artifacts: missing details on workloads, datasets, knob sets, hardware environments, and released code/scripts to enable replication and community validation.

- Benchmarking protocol: “fairer benchmarking” claim without a standardized, objective tuning protocol (e.g., test budgets, stopping rules, reporting requirements) to prevent cherry-picking.

- Multi-tenant environments: no consideration of contention in shared clusters and how tuning affects or respects neighboring workloads and fairness policies.

- Energy and cost impacts: unmeasured effects on power consumption, dollar costs, or carbon footprint; opportunity for cost-aware/energy-aware tuning objectives.

- Security and compliance: log replay in staging not assessed for privacy/PII risks or data governance constraints; no guidance on safe data handling during workload generation.

- Integration details: limited specification of the system manipulator and workload generator APIs, plugin model, access control, and deployment automation for diverse SUTs.

- Robustness across data scales: no study of whether tuned configurations remain effective as data size, cardinality, or skew change; lack of stability/transfer tests.

- Stop criteria and confidence: no definition of stopping conditions (performance plateau, statistical significance), or policies for validating “best” configurations before acceptance.

- Handling configuration interactions: no explicit detection or modeling of higher-order parameter interactions that may dominate performance, nor strategies to target them.

- Impact on reliability: tuning may affect stability (e.g., GC settings, cache policies); no assessment of error rates, failure modes, or resilience under stress.

- Governance and user control: no discussion of user intent, policy constraints, or guardrails (e.g., “do not change these knobs,” compliance limits) in automated tuning.

These gaps suggest opportunities for rigorous theory, broader empirical validation, safer and more adaptive deployment practices, and richer optimization formulations that reflect real-world constraints and objectives.

Collections

Sign up for free to add this paper to one or more collections.